Why career practitioners should also be critical adult educators

February 4, 2020

Career successes and challenges of immigrant professionals in Canada

February 4, 2020Virtual tools such as gamification can help bring personalized career development to underserved populations

Ronda Ansted

Two of the largest social justice issues in Canada are poverty and urban income inequality (Abedi, 2017; Canadian Poverty Institute, n.d.). Career development professionals have the tools, resources, information and connections to directly address these challenges by guiding people to poverty-ending employment.

This is not an easy or simple task. Poverty and income inequality stem from a host of interrelated circumstances and there are multiple obstacles to overcome. This article will focus on one aspect of addressing poverty, inequality and injustice: providing career information and guidance to people without easy access to them.

Career decision-making for the masses

Most people get their career information and chart their future by observing the people in their lives and making decisions based on what they know. If they are living in families and communities surrounded by unemployment or low-paying jobs, this will influence their thinking about what kind of future they can expect. Mass media can and does expand this horizon, but much of what is portrayed is also limited to occupations such as doctors, nurses, police investigators, TV executives or athletes. These influences can create a disconnect between a person’s capabilities and their career aspirations.

Career professionals address this disconnect by expanding people’s exposure to the world of work; assessing their innate strengths, preferences, abilities and interests; guiding their career decision-making process; and coaching them to develop effective job-search strategies. This process, while effective, takes time and resources.

There are simply not enough individuals in the career profession to reach every person who needs assistance. This is where strategic use of information and communications technology can reach people who are unable to get the career guidance they need, either because of resources or geographic distance. Since internet connection now reaches 96% of Canadians (Clement, 2019), leveraging online tools and making them engaging and user-friendly can be a powerful way to reach the underserved. (It should be noted, however, that many living in rural and remote parts of Canada still do not have access to reliable, high-speed internet access. [Black, 2019])

The challenges technology can address

Reaching and serving poor and rural populations needs to be more than simply putting information online. Career information and content is already available through websites and job boards. Many career assessments are available online as well, at variable price points from free to hundreds of dollars. Although high price points can be a significant obstacle to some, another challenge is making the content personalized and actionable. If content appears to be irrelevant, then people cannot easily integrate the information into their lives. If there are no clear, achievable and specific next steps, then people tend not to act (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009).

For example, someone who needs a job but doesn’t have career guidance can google “I need a job” which elicits over 17 billion results. The top results may be job boards or irrelevant suggestions. The overwhelming number of possibilities makes much of the information available unusable. How can a jobseeker tell if a job is good for them or not? How can they tell if the opportunity is legitimate? If they find a job they like, how can they set themselves up for a successful application? Just because the information is available doesn’t mean that it is useful.

In addition, not everyone processes information the same way. The written word or videos may be the simplest way to communicate, but many people need to engage with the content to learn something new. Fortunately, technology can facilitate personalized ways to explore and use content. Video games, including mobile phone games, are popular and touch every demographic (WePC, 2019).

One reason for this reach is that game designers find ways to include motivators for all types of people. Video games may allow you to compete with others, create new worlds, participate in a quest, collect items of value, gain mastery in a new skill or make something delightfully absurd happen. Game-design thinking has been used outside of the gaming industry to engage potential customers (think Facebook), but also to educate and support healthier behaviour. This process is called gamification.

The potential of gamification

Gamification is especially popular in educational settings and research indicates that it can foster curiosity, problem-solving and optimism (Faiella & Ricciardi, 2015). A tablet-based multiplayer program for teenagers helped them make healthy and prosocial decisions and demonstrated more engagement and motivation to participate as compared to the standard curriculum (Schoech, Boyas, Black, & Elias-Lambert, 2013).

These types of programs tend to use game-like elements such as points, badges, levels, story-telling, collaboration, progressive challenges and mystery to entice and engage users. In addition, they use different strategies to reach different types of people. Gamification can turn an ordinary task or series of tasks into something fun, challenging and rewarding. It can also tap into intrinsic motivation (McGonigal, 2011).

Research indicates that information and communication technology is a viable method to serve poor or rural populations (Dent, Ansted, & Aasen, 2018). Gamification research demonstrates that learning and behaviour change can be affected by well-designed programs. Pairing the two has the potential to provide high-quality, accessible, actionable and personalized career guidance to anyone with a smartphone or internet connection.

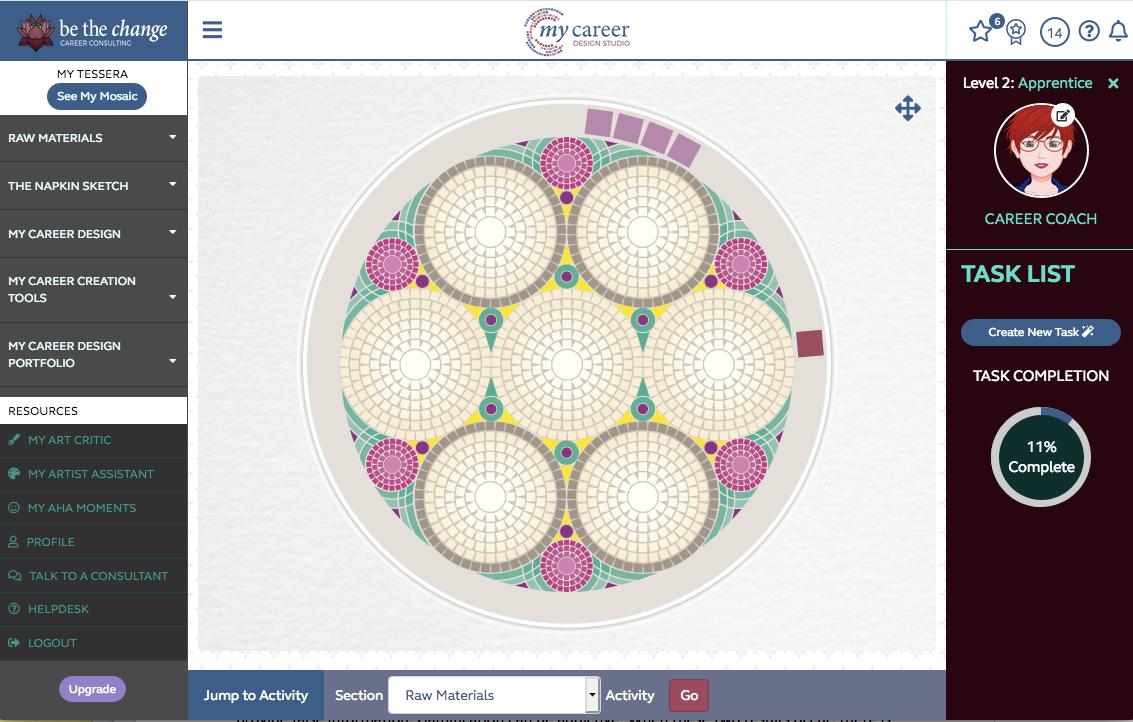

My Career Design Studio

An example of gamification is My Career Design Studio, an online program I developed. While completing common career assessments and activities, users gain points, level up and create a virtual work of art with an inspirational and customized message that they can see when they’ve completed all of the activities.

I created My Career Design Studio for two reasons. One, I wanted to tap into that element that makes computer games so addictive to help people stick with the difficult work of finding the elusive “right-fit” career. Two, I wanted to provide an affordable, high-quality product that could reach people who couldn’t afford to work with a career professional directly.

Based on classic career development theories, My Career Design Studio guides users to start with self-reflection, then to research different career possibilities, match careers with their goals and priorities, develop job search strategies, network, write a compelling resume and prepare for their interviews. The program creates a space for the users to become designers of their future lives and to create their own epic masterpiece, both virtually and in real life.

Considerations for strategic use of technology

Neither technology nor gamification can address all social injustice issues. In fact, there are many ways that they are currently being implemented to the user’s detriment. Technology can provide false information. Gamification can be addictive. When these two results occur, there is generally an agenda at play: buy stuff.

When looking for social justice outcomes through career guidance, there are a few important considerations. Know the population you are trying to serve. What are their needs? What are their challenges? Design your program with the view to serve as many people as possible by understanding different ways of learning and engaging with technology. Use the minimum amount of technological features and complexity to reach your population. The more complex the techology, the easier things go haywire. Finally, look for non-advertising revenues to support the program so users can focus on their future without distractions. When working with underserved population, their challenges are vast and intertwined. Look for ways not to add any more.

Using technology to facilitate social justice goals is not a simple task. However, technology and gamification are powerful tools and deserve to be used in service of guiding people to meaningful work, pathways out of poverty and a rewarding life.

Dr Ronda Ansted is a career consultant in private practice and the founder of Be the Change Career Consulting, focusing on people in the social impact arenas. She developed My Career Design Studio (careerdesign.studio), a gamified career coaching app that has been used all over the world with people and at all economic levels. She believes in the power of right-fit careers to create positive social change.

References

Abedi, M. (2017, July 14). Rise of income inequality in Canada ‘almost exclusive’ to major cities: study. Retrieved from Global News: globalnews.ca/news/3599083/income-inequality-canada-cities/

Black, R. (2019, October 24). All Canadians deserve reliable high-speed internet. Retrieved from policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/october-2019/all-canadians-deserve-reliable-high-speed-internet/

Canadian Poverty Institute. (n/d). Poverty in Canada. Retrieved from CPI: povertyinstitute.ca/poverty-canada

Clement, J. (2019, October 17). Number of internet users in Canada from 2000 to 2019 (in millions). Retrieved October 2019, from Statistica: statista.com/statistics/243808/number-of-internet-users-in-canada/

Dent, E., Ansted, R., & Aasen, C. (2018). Profit and Social Value: An Analysis of Strategies and Sustainability at the Base of the Pyramid. Journal of International & Interdisciplinary Business Research, 5(7), 110-137.

Faiella, F., & Ricciardi, M. (2015). Gamification and learning: A review of issues and research. Journal of E-Learning & Knowledge Society, 11(3), 13-21.

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Books.

Schoech, D., Boyas, J. F., Black, B. M., & Elias-Lambert, N. (2013). Gamification for behavior change: Lessons from developing a social, multiuser, web-tablet based prevention game for youths. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 31(3), 197-217.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New York: Penguin Books.

WePC. (2019, June 1). 2019 Video Game Industry Statistics, Trends & Data. Retrieved from WePC: wepc.com/news/video-game-statistics/