Reimagining tomorrow’s agriculture to attract and retain youth

June 9, 2020

North American rural workforce development: Poised for growth

June 9, 2020While each rural community is unique, common challenges and opportunities exist, including labour shortages and rising senior care needs

Ray Bollman

This article addresses the implications of rurality and specific influences on workforce development in rural Canada, such as labour shortages and the growing Indigenous population.

1. The degree of rurality matters

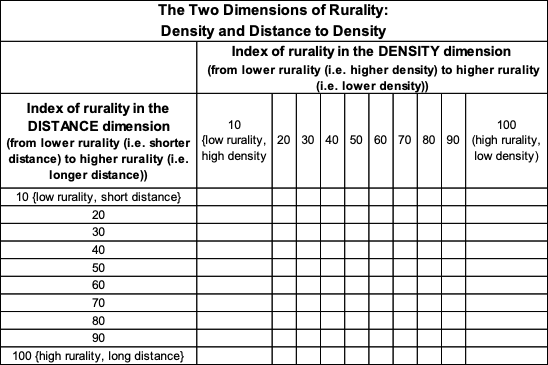

Every rural workforce policy or program must first consider the two dimensions of rurality:

- What is the size of your community? and

- What is the distance to a larger community? (Reimer and Bollman (2010), Bollman and Reimer (2018), Bollman and Reimer (2019) (See Figure 1).

The policy and practice of workforce development will differ depending on these rurality dimensions. While people living in rural areas understand the advantages and disadvantages of these characteristics, workforce policy analysts may not intuitively appreciate the implications.

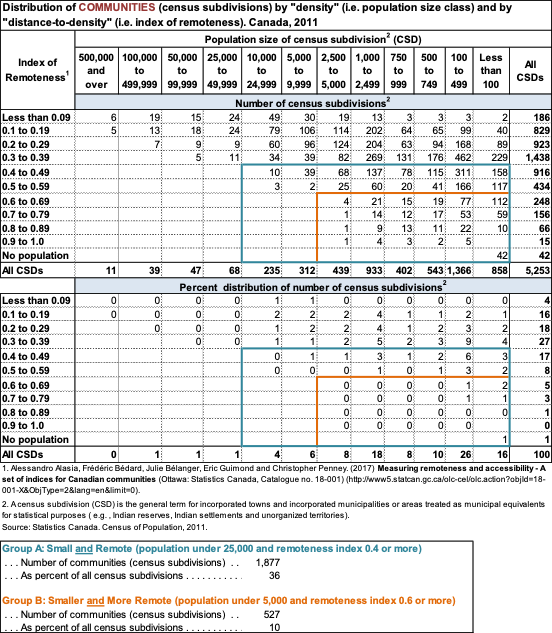

In the upper panel of Figure 2, we show the target clientele for rural workforce development in terms of the number of communities at each intersection of the dimensions of rural (ie, size of community and distance to a large community). The lower panel shows the target clientele in terms of the number of residents in each type of community for rural workforce development efforts across the rurality dimensions.

What is rurality?

We identify two spatial dimensions of rurality:

- Density (population size of a locality); and

- Distance-to-density

These are the two spatial dimensions shown in Figure 1 where any given locality could be located at any combination of “density” and “distance-to-density.” The location of a community in the grid of Figure 1 determines the spatial constraints (and advantages) of the given community. [See Reimer and Bollman (2010), Bollman and Reimer (2018) and Bollman and Reimer (2019)]

1. The degree of rurality matters

Every rural workforce policy or program must first consider the two dimensions of rurality:

- What is the size of your community? and

- What is the distance to a larger community? (Reimer and Bollman (2010), Bollman and Reimer (2018), Bollman and Reimer (2019) (See Figure 1).

The policy and practice of workforce development will differ depending on these rurality dimensions. While people living in rural areas understand the advantages and disadvantages of these characteristics, workforce policy analysts may not intuitively appreciate the implications.

In the upper panel of Figure 2, we show the target clientele for rural workforce development in terms of the number of communities at each intersection of the dimensions of rural (ie, size of community and distance to a large community). The lower panel shows the target clientele in terms of the number of residents in each type of community for rural workforce development efforts across the rurality dimensions.

Figure 1

Figure 2

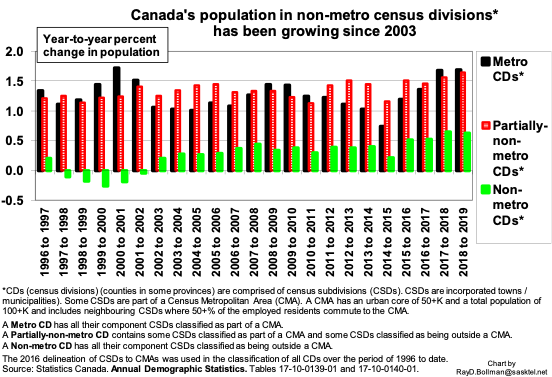

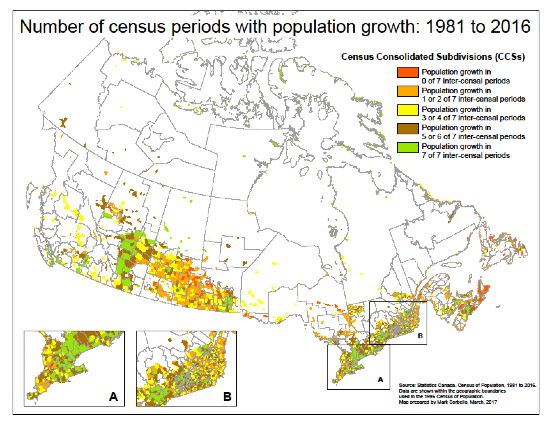

2. Rural Canada is growing

The fact that rural Canada is growing is important to our understanding of rural workforce development (Mendelson and Bollman (1998); Bollman and Clemenson (2008); Bollman (2012); Bollman (2017) (Figure 3). However, it is not growing as fast as urban Canada and thus the share of the population residing in rural areas is declining. Also, rural Canada is not growing everywhere – specifically, the rural population is growing near cities, in cottage country and in the North due to higher fertility rates among Indigenous women (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Figure 4

3. Labour market shortages are everywhere

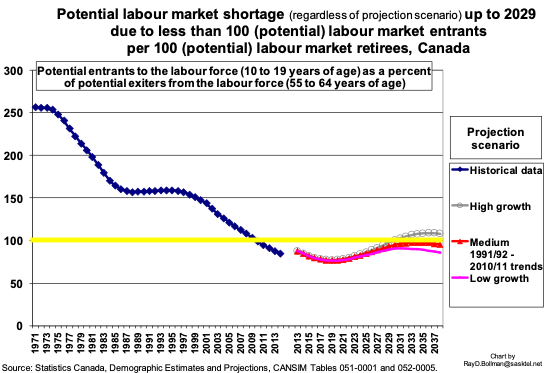

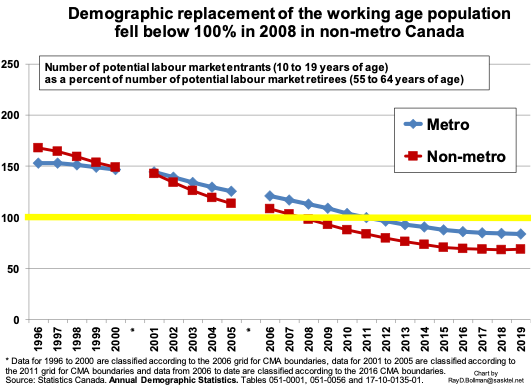

Rural workforce development has recently entered an era where there are fewer potential labour market entrants than potential retirees from the labour market. In the early 1970s, there were 250 potential entrants per 100 potential retirees across urban and rural areas (Figure 5). Now, in rural Canada, we see about 70 potential entrants for every 100 potential retirees (compared to 85 potential entrants in the urban labour market) (Figure 6). This implies labour shortages everywhere. As noted on the cover page of Bollman (2014), the rural development objective has switched from “create jobs” to “create people.”

Thus, individuals pursuing policy and programs may have a different personal experience of entering the labour market compared to the current entrants to the (rural) workforce. Understanding the data – rather than relying on personal experience – can help ensure workforce development initiatives are relevant for today.

Figure 5

Figure 6

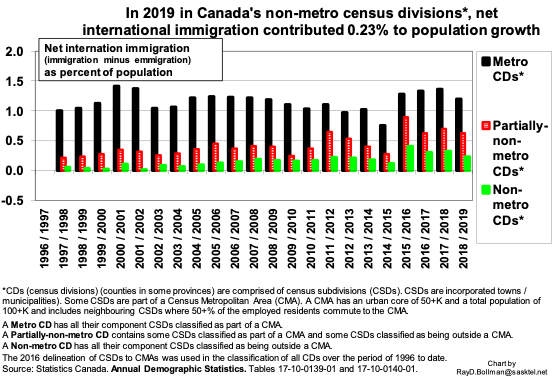

4. Immigrants are the source for growing the rural workforce

A quick review of demographic data show that:

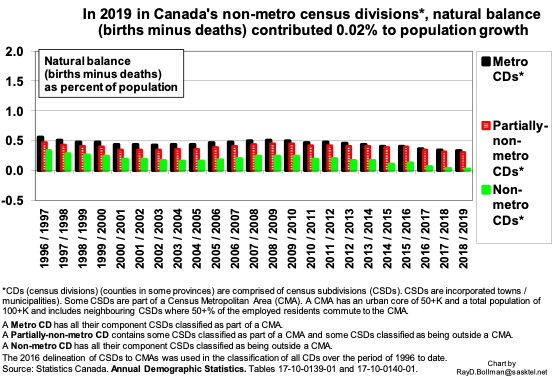

- In rural Canada, the number of births barely outpace the number of deaths (Figure 7) and in many parts of rural Canada, there are more deaths than births in each year;

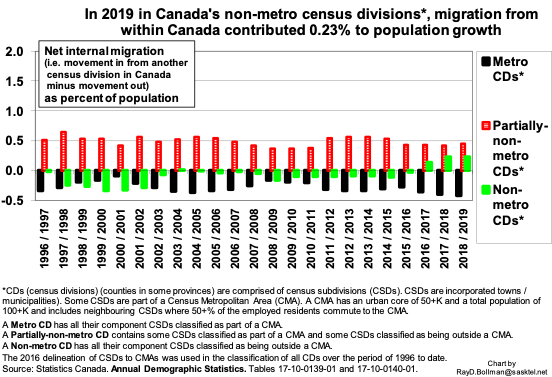

- Migration into rural Canada from elsewhere in Canada has been negative but is now a small positive contribution to rural population growth (Figure 8); and

- International immigration into rural Canada is now a small positive contribution to population growth (Figure 9).

Given the fact that deaths are outpacing births and that attracting a Canadian citizen to move to your community is a loss for another area, immigration can be a powerful source to grow the rural workforce.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

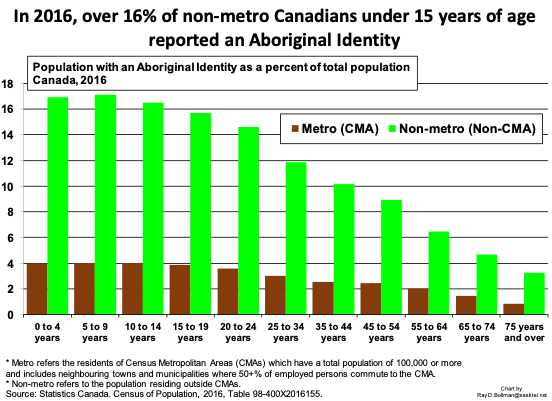

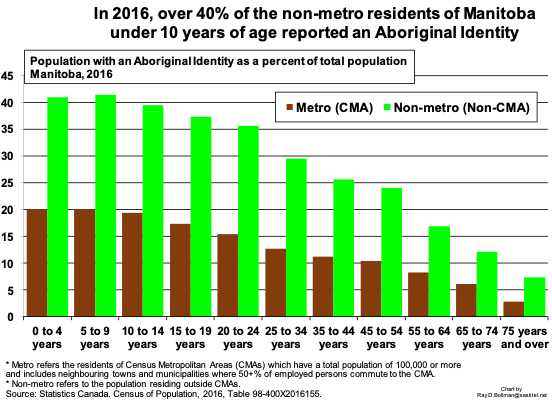

5. Indigenous young adults represent an increasing share of potential rural workforce entrants

Another feature of the rural workforce is that Indigenous people represent an increasing share of entrants to the rural workforce. At present, about 16% of potential rural labour market entrants in Canada report an Aboriginal Identity (Figure 10). This varies considerably across rural Canada. For instance, in rural Manitoba, about 40% of potential labour market entrants report an Aboriginal identity (Figure 11). Manitoba’s rural workforce will decline without the participation of Indigenous peoples. Successful Indigenous workforce development initiatives will define successful rural development in Manitoba, and other areas, going forward.

Figure 10

Figure 11

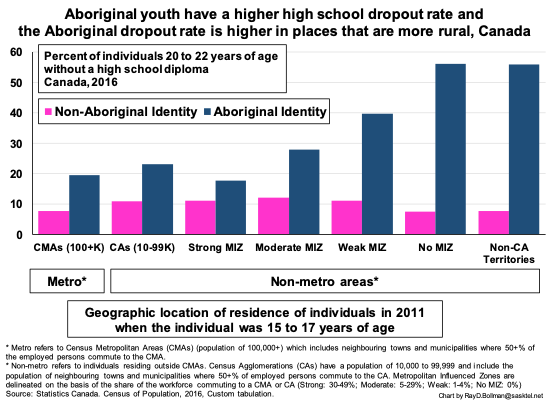

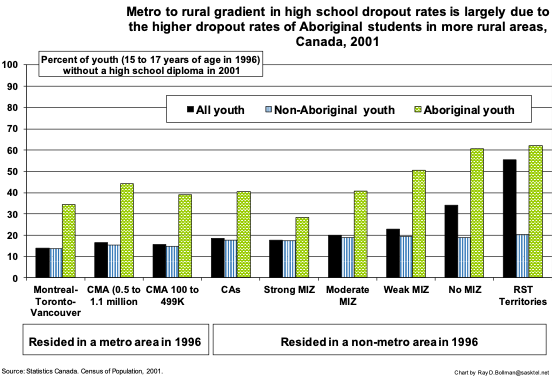

6. High-school non-completion rates

It is often assumed that high school drop-out rates are higher in rural areas. However, for non-Indigenous youth, high school non-completion rates are the same across the urban-rural spectrum (Figure 12). For Indigenous students, non-completion rates are higher in urban areas compared with non-Indigenous students, and much higher in rural areas. Thus, the “common knowledge” that high-school completion rates are higher in rural areas is due to a higher share of Indigenous students in rural areas and higher high school non-completion rates among Indigenous students. The same situation existed 15 years ago (Figure 13).

Figure 12

Both the federal and the provincial educational systems have failed Indigenous youth (Angus, 2017). In my opinion, the (potential) entry of Indigenous youth into the rural labour market represents the major challenge for policy development and program delivery for rural workforce development for two reasons:

- Their demographic impact represents the sole source for maintaining the size of the rural market (in many jurisdictions); and

- Their lower high-school completion rates may be expected to constrain their options in the labour market.

Figure 13

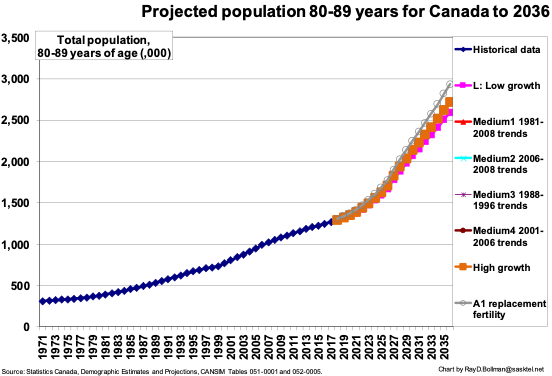

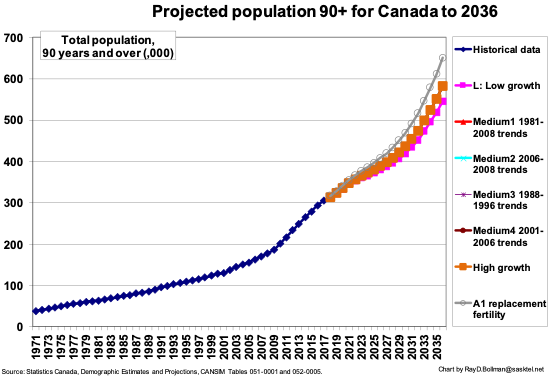

7. Senior care needs are rising

Finally, one occupation with an expanding demand in rural and urban communities is senior care. In Canada, the number of individuals ages 80-89 and ages 90+ is expected to double over the next 20 years (Figures 14 and 15). Individuals in the latter age group will require a higher level of residential care. Rural communities have an opportunity to build residences for seniors, both for local seniors and for seniors outside of their community. Workforce development needs to actively engage in this opportunity.

Figure 14

Figure 15

To conclude

Rural is not all the same. Understanding the distinct features of rural communities will inform successful policy development and program delivery in rural workforce development. The rurality dimensions of community size and the distance of the community to a large centre defines the specific constraints (and opportunities) for workforce development in any given locality. What is the role of immigration, Indigenous workforce inclusion or demographic shifts? Rural workforce development must recognize the impact of these trends and others to develop solutions that resonate in the local context.

Ray Bollman has retired from Statistics Canada, where he was the founding editor of Statistics Canada’s Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletins. Since retiring, he has been writing the series of bulletins titled Focus on Rural Ontario for the Rural Ontario Institute and has authored a report for the Federation of Canada Municipalities titled Rural Canada 2013: An Update – A statement of the current structure and trends in Rural Canada. Presently, he is a Research Affiliate with the Rural Development Institute, Brandon University and a Research Affiliate with The Leslie Harris Centre of Regional Policy and Development, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

References

Alasia, Alessandro. (2004) “Mapping the Socio-economic Diversity of Rural Canada.” Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Vol. 5, No. 2 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE). (http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/olc-cel/olc.action?objId=21-006-X&objType=2&lang=en&limit=0).

Alasia, Alessandro, Ray D. Bollman, John Parkins and Bill Reimer. (2008) An Index of Community Vulnerability: Conceptual Framework and an Application to Population and Employment Change. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Agriculture and Rural Working Paper no. 88, Catalogue no. 21-601-MIE) (www.statcan.ca/cgi-bin/downpub/listpub.cgi?catno=21-601-MIE).

Alasia, Alessandro. (2010) “Population Change Across Canadian Communities: The Role of Sector Restructuring, Agglomeration, Diversification and Human Capital.” Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Vol. 8, No. 4 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE). (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?catno=21-006-X&CHROPG=1&lang=eng)

Angus, Charlie (2017) Children of the Broken Treaty (Regina: University of Regina Press, second edition).

Bernard, André. (2008) “Immigrants in the hinterlands.” Perspectives on labour and income. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 75-0001, January), pp. 5 to 14.

Beshiri, Roland and Emily Alfred. (2002) “Immigrants in Rural Canada.” Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Vol. 4, No. 2 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE) (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?catno=21-006-X&CHROPG=1&lang=eng).

Beshiri, Roland. (2004) “Immigrants in Rural Canada: 2001 Update.” Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Vol. 5, No. 4 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE) (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?catno=21-006-X&CHROPG=1&lang=eng).

Beshiri, Roland and Ray D. Bollman. (2005) Immigrants in Rural Canada. Presentation to the 2005 Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation – Rural Development Institute National Rural Think Tank (https://www.brandonu.ca/rdi/wp-content/blogs.dir/116/files/2015/09/Immigrants_in_Rural_Canada.pdf).

Beshiri, Roland and Jiaosheng He. (2009) “Immigrants in Rural Canada: 2006.” Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Vol. 8, No. 2 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE) (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?catno=21-006-X&CHROPG=1&lang=eng).

Bollman, Ray D., Roland Beshiri and Heather Clemenson. (2007) “Immigrants in Rural Canada.” In Bill Reimer (ed.) Our Diverse Cities No. 3 (Summer), pp. 9 – 15.

Bollman, Ray D. and Heather A. Clemenson (2008) Structure and Change in Canada’s Rural Demography: An Update to 2006 with Provincial Detail (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Agriculture and Rural Working Paper No. 90, Catalogue no. 21-601-MIE) (http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2008/statcan/21-601-M/21-601-m2008090-eng.pdf).

Bollman, Ray D. (2012) Canada’s rural population is growing: A rural demography update to 2011 (Guelph: Rural Ontario Institute) (http://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/file.aspx?id=231b5f1a-a7ca-4ddf-b69e-4034a35de640).

Bollman, Ray D. (2013) “Factsheet: Location of Immigrant Arrivals in 2012.” Pathways to Prosperity Bulletin (London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario, Pan-Canadian Project on “Pathways to Prosperity: Promoting Welcoming Communities in Canada”, May, pp. 2-4). (http://p2pcanada.ca/library/factsheet-location-of-immigrant-arrivals-in-2012).

Bollman, Ray D. (2013) “Factsheet: Immigrants – Where are They Living Now?” Pathways to Prosperity Bulletin (London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario, Pan-Canadian Project on “Pathways to Prosperity: Promoting Welcoming Communities in Canada”, October, pp. 6-9).(http://p2pcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/eBulletin-October-2013.pdf)

Bollman, Ray D. (2013) “Immigrant arrivals in 2012.” Focus on Rural Ontario (Vol. 1, No. 6, July) (http://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/uploads/userfiles/files/Focus%20on%20Rural%20Ontario%20-%20Overview%20of%20rural%20ON%20geography.pdf

Bollman, Ray D. (2013) “Where are immigrants residing now?” Focus on Rural Ontario (Vol. 1, No. 7, July) (http://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/uploads/userfiles/files/Focus%20on%20Rural%20Ontario%20-%20Overview%20of%20rural%20ON%20geography.pdf

Bollman, Ray D. (2013) “Aboriginal identity population.” Focus on Rural Ontario (Vol. 1, No. 9, July) (http://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/uploads/userfiles/files/Focus%20on%20Rural%20Ontario%20-%20Overview%20of%20rural%20ON%20geography.pdf).

Bollman, Ray D. (2013) Canada’s rural labour market and the role of immigrants. Presentation to the Annual Rural Policy Conference of the Canadian Rural Revitalisation Foundation, October 24 to 26, Thunder Bay, Ontario. Available at http://www.crrf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/B3-Rural-Immigration-Migration-Presenter-Ray-Bollman.pdf.

Bollman, Ray D. and William Ashton. (2014) Aboriginal Population (Brandon: Brandon University, Rural Development Institute FactSheet) FactSheets at (http://www.brandonu.ca/rdi/25th/).

Bollman, Ray D. and William Ashton. (2014) Immigrant Arrivals (Brandon: Brandon University, Rural Development Institute FactSheet) FactSheets at (http://www.brandonu.ca/rdi/25th/).

Bollman, Ray D. (2014) “Factsheet: Location of Immigrant Arrivals in 2013.” Pathways to Prosperity Bulletin (London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario, Pan-Canadian Project on “Pathways to Prosperity: Promoting Welcoming Communities in Canada”, May, pp. 8-12). (http://p2pcanada.ca/wp-content/blogs.dir/1/files/2014/05/eBulletin-May-2014.pdf)

Bollman, Ray D. (2014) Rural Canada 2013: An Update — A statement of the current structure and trends in Rural Canada. Paper prepared for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. (http://crrf.ca/rural-canada-2013-an-update/)

Bollman, Ray D. (2015) “Factsheet: Hot Spots of Recent Immigrant Arrivals at the Community Level in Canada.” Pathways to Prosperity Bulletin (London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario, Pan-Canadian Project on “Pathways to Prosperity: Promoting Welcoming Communities in Canada”, January, pp.10-12). (http://p2pcanada.ca/wp-content/blogs.dir/1/files/2015/01/eBulletin-January-2015.pdf).

Bollman, Ray D. (2016) Maps of sub-provincial demographic levels and trends annually to 2015 (http://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/uploads/userfiles/files/Maps%20of%20Sub-provincial%20Demography%20to%20July%202015%20-%20Updated%20Feb%202016%20-%201.pdf)

Bollman, Ray D. (2017) Rural Demographic Update: 2016 (Guelph: Rural Ontario Institute) (http://www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/file.aspx?id=26acac18-6d6e-4fc5-8be6-c16d326305fe).

Bollman, Ray D. and Bill Reimer. (2018) The dimensions of rurality: Implications for classifying inhabitants as ‘rural’, implications for rural policy and implications for rural indicators. Paper presented to the 30th International Conference of Agricultural Economists, July 28 to August 2, Vancouver (https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/277251/files/1467.pdf).