Career briefs

May 30, 2019

Editor’s note

June 5, 2019How do new ways of working with clients get legitimized in the career development field? The OneLifeTools origin story offers some clues

Ali Breen

This article is based on an interview the author conducted with Mark Franklin, Co-founder of OneLifeTools and Practice Leader at CareerCycles.

How does a new assessment system become a standard, accepted method of practice?

As practitioners, we all learn theories and approaches to practice that have been widely adopted and used for decades. But what about new tools and assessments? How do new ways of working with clients get legitimized in our field?

These scenes from the OneLifeTools origin story aim to answer this question and paint a picture of innovating the field of career development from the inside out.

The lightbulb moment

We start with an engineer-turned-career-practitioner, frustrated as he reviews his scribbled notes in a campus counselling office. His notebook is filled with important data, repeating patterns and captured lightbulb moments from clients.

We cut to our career practitioner having his own lightbulb moment. After countless clients tell him stories about their lived experiences, he begins to see patterns emerge. Key elements are consistently revealed and explored, such as a client’s desires, strengths and personal qualities. They bring up the influence of other people on their education, life and work decisions.

He begins to use a flipchart, divided into quadrants, that pull out these elements – client after client, story after story. Then, the epiphany: “This is a systems approach. I can harness these stories and organize them so clients can reflect and power up their next steps!”

As helping professionals, we all innovate. With each new client we adapt the techniques and tools we have at our disposal to support the career development process. We synthesize our experiences and ideas, and other people’s ideas, too.

Arriving in the counselling world after a 10-year career in engineering, Mark Franklin’s transferable skills in systems thinking and engineering problem-solving paved the way for developing a new approach at the intersection of career counselling and systems. When he started in the career field, Mark says he was keen to learn everything he could, drawing on narrative experts like Michael White, (for example, White et al., 1990) and those who brought narrative ideas to career counselling, such as Mark L. Savickas (2012). To help clients navigate a lifetime of transitions, he integrated William Bridges’ change model (2004), Jim Bright and Robert Pryor’s chaos theory of careers (2011), Herminia Ibarra’s working identity (2004), and Kathleen E. Mitchell, Al S. Levin and John D. Krumboltz’s Happenstance approach (Mitchell et al., 1999). To foster a supportive mindset, he mixed in the work of positive psychologists such as Barbara L. Fredrickson (2001).

He also focused on the career counselling area of specialization in the Canadian Standards & Guidelines for Career Development Practitioners. This area tells practitioners to “demonstrate method of practice in interactions with clients, and to develop a method of practice that is grounded in established or recognized ideas” (The Canadian Council for Career Development & Canadian Career Development Foundation, 2012).

The next practitioner

It’s wonderful when something works well for us as practitioners. But can it work for others? Can it move from the confines of one office and expand out into the world?

So, Mark shares his innovation with a trusted peer, Leigh Anne Saxe:

“A system is made from interdependent parts that form a unified whole. A systems approach breaks things down into linked processes, with inputs and outputs.

In a narrative client session, the most important inputs are clients’ stories, their lived experiences, their present situation and their questions. For example, “I studied tech, I moved into video game development, but now I’m burnt out. What should I do next?” Additional inputs include the support and knowledge of a career professional, the feedback of trusted allies, and the results of informational interviews and field research conducted by the client.

The outputs are, within the OneLifeTools/CareerCycles framework, a Clarification Sketch, the main innovation at the heart of the system. It gathers and organizes client inputs into a visual representation, co-created by client and practitioner, which is divided into seven elements: desires, strengths, personal qualities, natural interests, assets, other people and possibilities. This leads to a second output, the Clarification Statement, which is a prioritized, forward-facing summary of the most important pieces of client stories, collected in the Sketch over the course of the coaching process.

The Clarification Statement acts as an output of the narrative clarification process, and as an input into the second, linked process of Intentional Exploration. Its output is Exploration Plans, based on taking inspired action that’s powered by the clarification gleaned by reflection on client stories using a systems approach.”

He demonstrates the same flip chart system he’s using with clients to Leigh Anne, and she tries it with her clients. It sticks. Mark trains a trusted handful of practitioners at his dining room table. It sticks with them, too.

The model that began on a flipchart becomes the Online Storyteller web application, a method of practice, a certification program and the basis for a clarification board game called Who You Are Matters!

A handful of practitioners adopt the narrative framework as their primary approach to client work. This is unique and disruptive. Often, the career development field focuses on quantitative assessments and derives models from theory. The OneLifeTools/CareerCycles framework is qualitative. It was born out of practice and moved into theory. It is now supported by peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters.

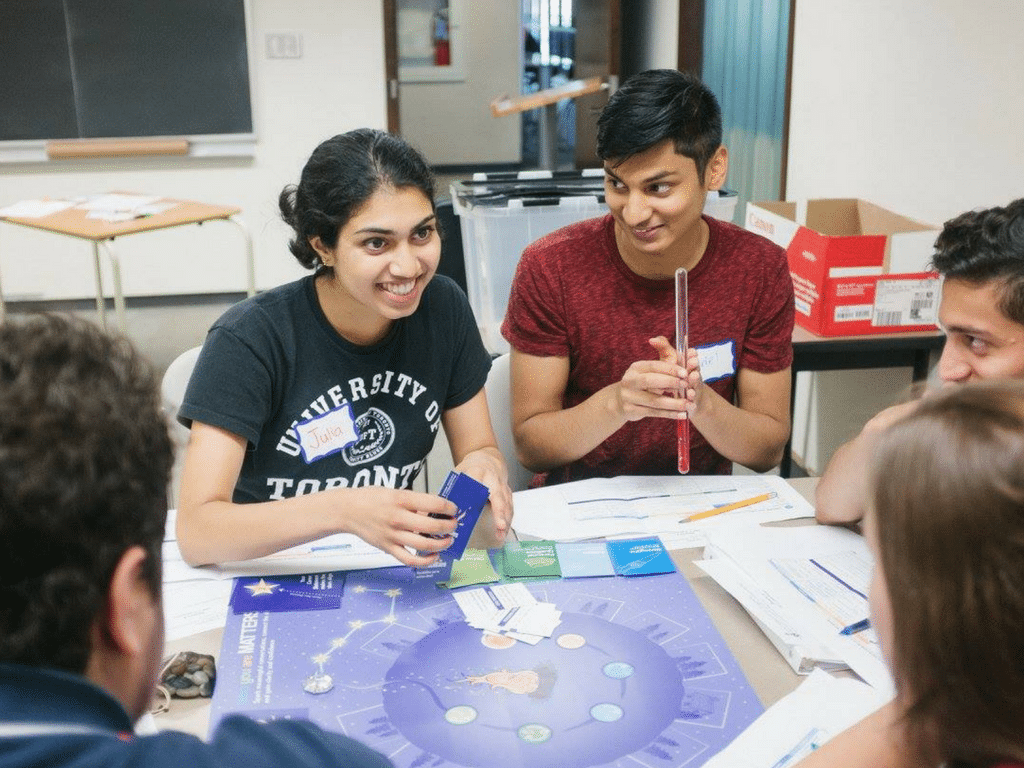

Students play the “Who You Are Matters!” board game.

The living room

With every change, there are change-makers.

In our last scene, Mark is facilitating training and introducing an early version of a narrative board game with a group of thought leaders in Rich Feller’s living room in Fort Collins, Colorado. Professor and former co-ordinator of Counseling and Career Development at Colorado State University, and former president of the National Career Development Association, Rich acts as a scout for innovative tools and techniques. Rich and Mark become friends and business co-founders.

They lean on other change-makers in their circles. A number of talented associates and helping professionals over the years contribute to peer-reviewed, evidence-based outcome studies. A community of practice is built, and the co-founders, supported by a talented team, seek out continued feedback to refine the narrative system, expand it, share it widely in conferences, writing and training, and to integrate it with other tools and assessments such as YouScience, MBTI, Holland codes, card sorts and more.

The answer

The career practitioner sitting frustrated in his office, the shared vision on a flipchart and the movement sparked in a living room. These three scenes all play a part in the OneLifeTools origin story, and in addressing our initial question: how does a new form of assessment get adopted as a standard?

The answers lie in the tools, the stories, the evidence, the theory and, most of all, the people. When practitioners are open to new ways of doing their work, the field evolves, just as the world evolves around us.

Millennials Career Coach Ali Breen believes that your career can and should be a reflection of who you are and how you want to be in the world. She uses story-based, narrative approaches and experiential learning in her Halifax private practice. As a past corporate recruiter and bilingual career practitioner in non-profit employment centres, Breen has spent a decade on both the demand & supply sides of the Career Management table. She also draws from her experiences as Community Growth Manager for OneLifeTools and as a member of 3CD’s Outreach and Advocacy Working Group.

References

Bridges, W. (2004). Transitions: Making sense of life’s changes. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Bright, J. E., & Pryor, R. G. (2011). The chaos theory of careers. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(4), 163-166.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American psychologist, 56(3), 218.

Ibarra, H. (2004). Working identity: Unconventional strategies for reinventing your career. Harvard Business Press.

Mitchell, K. E., Al Levin, S., & Krumboltz, J. D. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(2), 115-124.

Savickas, M. L. (2012). Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(1), 13-19.

The Canadian Council for Career Development & Canadian Career Development Foundation. (2012). Canadian Standards and Guidelines for Career Development Practitioners – Areas of Specialization – Career Counselling [PDF] Retrieved from: http://career-dev-guidelines.org//wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Career-Counselling.pdf

White, M., White, M. K., Wijaya, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. WW Norton & Company.