How COVID-19 is affecting rural communities across Canada

Travel and business restrictions related to the pandemic have hit some rural jobseekers and industries hard, but there is hope on the horizon

Lindsay Purchase

When Selkirk College Instructor Adela Tesarek Kincaid began working with BC communities to help them develop economic resilience plans last year, she had no way of knowing how urgently they would be needed some months later. Initially intended to help keep economies moving after natural disasters, the focus has now shifted to pandemic preparedness.

When Selkirk College Instructor Adela Tesarek Kincaid began working with BC communities to help them develop economic resilience plans last year, she had no way of knowing how urgently they would be needed some months later. Initially intended to help keep economies moving after natural disasters, the focus has now shifted to pandemic preparedness.

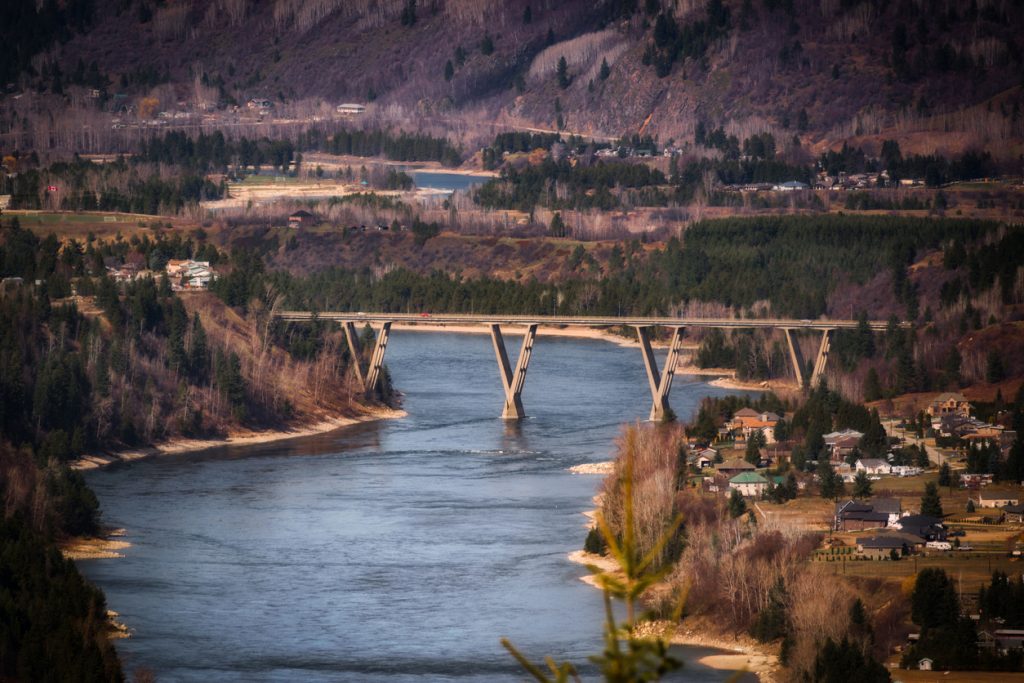

“I think we’ll be that much better prepared now and going into the future. So I think that’s definitely a strength and a good thing that came out of this,” says Tesarek Kincaid, who is also a Faculty Researcher at the College, located in the West Kootenay region of BC. Local communities drove the creation of the resilience plans with the support of staff and students from Selkirk and Simon Fraser University, alongside Community Futures Central Kootenay.

Unfortunately, there is no single blueprint for dealing with an unprecedented global pandemic, and Canada’s rural communities – each with their own strengths and challenges, unique demographic makeups and industries – will have to chart a path forward while the ground is still shifting beneath them. Here’s how rural areas and industries are being affected by COVID-19 across Canada, and what they believe will help them get through it.

At-risk industries

The lessons of previous economic recessions suggest that communities will experience the crisis differently, depending on how remote they are, their level of community capacity and their economic mix (Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation, 2020). However, it is expected that certain industries will be hit harder.

Tourism is one such industry. In 2016, one in 10 Canadian workers was employed in tourism, with nearly 20% of the sector located in rural areas (Tourism HR Canada, n.d.).

Philip Mondor, President and CEO, Tourism HR Canada, says that rural areas relying heavily on tourism may face a longer recovery period. “These were some of the first areas to be shuttered and they’re going to be some of the last to open and there’s lots of very sensible reasons for that,” he says. Communities – especially those with large proportions of vulnerable populations – may not have the resources to deal with a sizeable outbreak. Even as physical distancing and travel restrictions are loosened, rural communities may continue to be more cautious.

More COVID-19 coverage on CareerWise

- Work-integrated learning can boost innovation and help us face COVID-19

- How to prepare for the post-pandemic world of careers work

- Work-from-home policies should be widespread post-pandemic

- Coping with career uncertainty in the time of COVID-19

This will also affect workers whose jobs are part of the broader tourism economy, Mondor says, such as a gas station attendant employed near a tourist hotspot. “People take for granted that some of the services they have are inherently there whether tourism is around or not. And indeed it’s not true.”

These challenges have started to bear out in the Yukon, which normally has a robust tourism sector but closed its borders to all non-essential travel in April.

“People in the service industry and the tourism industry are just being hit incredibly hard. I think that’s a really big challenge,” says Lana Selbee, Executive Director of Yukonstruct, a Whitehorse non-profit and hub that supports local makers and entrepreneurs.

The territory has plans to lift lift travel restrictions between Yukon and BC on July 1, but in the meantime, it’s looking to other solutions. Selbee says officials and the provincial tourism association are encouraging Yukoners to get out and explore – to be tourists in their own territory to support local businesses.

Across the country in New Brunswick, when the high tourism season would normally be getting under way, closed borders are expected to hurt students and seasonal workers. However, the effects of the pandemic have been more immediate in other sectors, says Charles LeBlanc, Manager, South East Region, Working NB.

The agriculture and fisheries sectors are experiencing a shortage of at least 1,200 workers, positions that would normally be filled by temporary foreign workers, Le Blanc says. Employers have raised wages in a bid to attract more domestic workers, while Working NB has created a new virtual job-matching platform to help boost recruitment.

In a province where 40% of agricultural workers are migrants, Ontario’s farmers are in a similar position (Statistics Canada a, 2020).

“I’m really worried about the farmers, really, really worried about them,” says Madelaine Currelly, CEO of the Community Training and Development Centre, which has locations in Peterborough and Cobourg, ON. “Some of them have been able to bring in international labour, which is what a lot of them have to do in order to survive, but the numbers are just not there where they used to be.”

Currelly is also concerned about the restaurants and shops of Cobourg’s downtown strip. She has spoken to employers who have had to lay off staff, while others have applied for federal funding to help them stay afloat. “It’s really important that the downtown is alive and well and thriving in order for the inhabitants to even have a place to go,” she says.

Students and jobseekers

Despite labour shortages in some areas, Canada’s unemployment rate hit 13.7% in May (Statistics Canada b, 2020). This has presented a major challenge for post-secondary students relying on summer employment to pay tuition and meet program requirements. Over one-third of students have reported having a work placement cancelled or delayed, while 48% of students say they lost a job or were temporarily laid off. (Learn more about the impact of the pandemic on students in this issue’s infographic, “COVID-19 and Canada’s post-secondary students“)

While Tesarek Kincaid has continued to employ research assistants, other students have faced cancelled placements or been unable to find work. “What students have shared with me is that they’re having a hard time amidst all the uncertainty knowing where they’re going to be able to have or gain [work] opportunities,” she says. Some students – not so keen on online learning – aren’t sure whether they’ll register for the next term.

Working NB has been hearing from many students who are concerned that their inability to find work will disqualify them from financial supports for the upcoming year. LeBlanc says WorkingNB’s employment counsellors are being “bombarded” by questions that they don’t have the answers to yet; the federal government will have to provide guidance around the number of insurable hours required to qualify for different programs. “When you’re looking at the recovery of the pandemic, short-term if they have no jobs, well, long-term it means they’re not pursuing education or training, because they don’t have the money to pay for those programs,” he says.

While funding opportunities have emerged for students in response to the pandemic – most notably, the federal Canada Emergency Student Benefit – it’s not yet clear how many students are falling through the cracks.

The long road ahead

The big question facing rural Canada right now is, what does recovery look like? In a recent report, the Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation (2020) emphasized the importance of “adopting place-based approaches” to support recovery and resilience. In other words, what is needed to move forward could look different for every community.

Mondor, of Tourism HR Canada, agrees that a community lens will inform next steps. “The strategy to recover employment is not going to be sectoral, per se, it’s going to be more practically, in a very organic way, a community-led concern,” he says.

Skills and infrastructure development, including improved broadband access in rural areas, also have a role to play. Leblanc says equipping people with digital skills has become a critical need. “The unusual and unprecedented nature of the crisis means that it is not only the more educated but also the ones who are in jobs and occupations more amenable to remote work who fare better,” he says. LeBlanc would like to see the government offer digital skills training courses as well as subsidize internet access and computer costs for those who cannot afford the technology.

While the pandemic has undoubtedly brought many challenges to the forefront, opportunities have arisen as well. In the Yukon, with supply chains disrupted and industries hit hard, the focus has shifted to how to better support local businesses and entrepreneurs. “I think for us, it’s really just asking ourselves the question of how do we show up in a different way for our members and the broader community?” Selbee says.

This kind of reflection is emblematic of the local entrepreneurial spirit that gives Selbee hope for recovery. “Crisis often creates a lot more innovation,” she adds.

The road to recovery will be long and hard, with some communities facing more obstacles than others. However, it also evident that across rural Canada, determination and creativity are alive and well. These resources will help communities rebuild – and be prepared to withstand whatever disruptors the future will hold.

Lindsay Purchase is CERIC’s Lead, Content, Learning & Development. She is the Editor of CERIC’s tri-annual magazine, Careering, and the CareerWise website, along with the CareerWise Weekly newsletter. She is always happy to chat about article ideas: lindsay@ceric.ca.

References

Canadian Rural Revitalization Foundation (2020). Supporting rural economic recovery & resilience after COVID-19. Retrieved from http://crrf.ca/covid19/

Statistics Canada, a. (2020). The distribution of temporary foreign workers across industries in Canada. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00028-eng.htm

Statistics Canada, b. (2020). Labour Force Survey, May 2020. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200605/dq200605a-eng.htm?HPA=1

Tourism HR Canada. (n.d.). Tourism Facts. Retrieved from http://tourismhr.ca/labour-market-information/tourism-facts/