7 steps to help clients futureproof their careers

June 22, 2021

Client Side: Grade 12 was tough enough. Then the pandemic hit

June 22, 2021Engaging with client emotion and understanding the context of a change response can help build a strong foundation

Karen Begemann

The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted many of our perspectives on change and transition. For over a year, we have witnessed and experienced unemployment, businesses shuttering and educational institutions pivoting to online learning. Unprecedented numbers of Canadians are working from home. The uncertainty and isolation have taken a toll on mental health.

However, with more Canadians getting vaccinated, hope has been gradually easing anxiety. We know there are available jobs and the opportunities will continue to grow. Classroom learning is finding its way back. Many workers are returning to the workplace (albeit on modified schedules). While these changes are positive, they also represent another transition to manage, which can bring up many emotions for us and for our clients. You may be wondering: How do I best address client emotion around transition? How can I develop a more change-ready mindset in myself and in my clients?

We are no strangers to transition

“Trying to place an evolving person into the changing work environment … is like trying to hit a butterfly with a boomerang.” – John Krumboltz (Bimrose,n.d.)

Career pivots are far from a new topic of conversation for career development professionals. Theorists such as Jim Bright and Robert Pryor (Chaos Theory of Careers), Nancy Schlossberg (Transition Theory) and the late John Krumboltz (Learning Theory of Career Counselling) have been addressing the impacts of chance and change on career development for over 20 years. However, we are now at an ideal time to fully embrace the notion of being change-ready.

Although there is a larger body of theoretical context we could consider, Kris Magnusson’s work addressing emotion in career helping and Schlossberg’s Transition Theory resonate strongly today. By drawing on theoretical and practical aspects of their work, we can offer our clients strategies to cope with change.

Read more

Book review: Don’t Stay in Your Lane an essential read for career counsellors

‘Hard to stay motivated’: Strategies to boost client momentum in job search

Justifying personal breaks in a professional context

Feelings, behaviours, thoughts: a cycle

In his keynote session at CERIC’s Cannexus21 conference, Magnusson challenged the assumption that emotion-focused work sits outside of career development practitioners’ professional boundaries: “Working with client emotion is not only within a practitioners’ scope of practice, it is an ethical obligation to do so” (Magnusson, 2021).

In the past year and a half, we have seen how the pandemic has taken a toll on the mental health of Canadians. Our youth and BIPOC populations and the LGBTQ+ communities have experienced the most significant effects (Statistics Canada, 2020). Students and jobseekers craving support often share the emotional toll of these experiences with us. While many career professionals have felt obligated to restrict our interventions to active listening, empathy and referral to mental health professionals, it is refreshing to hear that not only can we engage client emotion in a more fulsome way, but that we have a professional duty to do so.

Although it is important to provide information and resources to our clients, they may not always be in a place to receive them – let alone make use of them – until we have addressed the emotions that accompany them to the session. Magnusson described three domains of change that clients cycle through: feelings, behaviours and thoughts. He recommends starting by addressing emotion. A client who comes into a session weighed down by the anxiety of financial pressures, for instance, may not feel excited about developing an action plan. The client is looking at the process through their emotion. Magnusson shares this quote by Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness: “We cannot feel good about an imaginary future when we are busy feeling bad about an actual present” (Magnusson, 2021).

Magnusson outlined three interventions to acknowledge emotion, all of which sit comfortably within our boundary of competency.

- Name the emotion. This can be done through reflective listening, exploring the impact of the emotion and by assisting the client to harness their emotion (i.e. to feel less or more of it ).

- “Acting as if” or, more commonly, “fake it until you make it.” For example, rather than encouraging the client to be more confident in their upcoming job interview, you can ask them to try out the behaviour of confidence in a practice interview.

- Reframing. This has the power of shifting a client’s mindset from a closed position to a more open and curious attitude. Once you have acknowledged the emotion, then the client will be far more receptive to considering and generating alternate ways of viewing their situation.

Factors that influence transition

Schlossberg has also contributed greatly to our understanding of how we experience change, from our perceptions to our coping strategies. Her Transition Theory defines a transition as an event or non-event that results in changed roles, relationships, routines and assumptions (Evans et al., 1998). As the meaning of a transition is unique to an individual, practitioners must consider the type of change, context (e.g. work, personal) and impact on the client (Evans et al., 1998).

Schlossberg 4 S’s – Situation, Self, Support and Strategies – serve as a model to understand the influences on an individual’s ability to cope during a transition (Anderson et al.,2012):

- Situation: trigger, timing, control over the transition, new role(s), duration of the transition, previous experience, perception, other stresses.

- Self: personal/demographic factors (e.g. gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity/culture, age, stage of life) and psychological resources (e.g. ego development, personal values, resiliency).

- Support: Supportive individuals can include family, friends, a mental health counsellor or a career professional, for example.

- Strategies: The ways individuals cope with the transition – responses that modify the situation, control the meaning of the problem and those that aid in managing stress.

The 4S model offers a context through which career practitioners can understand the complexity of factors facing our clients. It is fully within our scope to engage clients with “Support” and “Strategies” related to the emotional ups and downs of their employment search and to guide them in next steps.

Conclusion

While we continue to adapt to shifting circumstances brought about by the pandemic, it is important to recognize that there is much we can do that is within our control. Engaging appropriately with client emotion can help clients to not only feel heard but to normalize their experience. By taking the time to understand the factors affecting clients’ responses to transition, we can build a foundation for developing a change-ready mindset. Identifying small steps can lead to action and forward progress. Our clients need our support as change agents now, more than ever.

3 exercises to help clients take action:

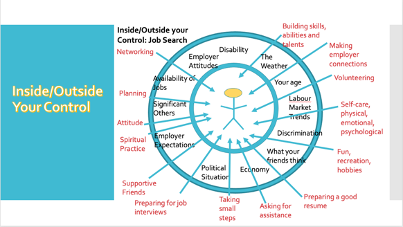

Inside/Outside your Control: A brainstorming exercise you can do to identify and list all the factors a client considers to be roadblocks to finding work. Ask the client what factors are within their control and which aren’t. Through brainstorming, expand the list of what they do have control over using action words (e.g. Talk to a supportive friend). Then, agree on one small action step they can take.

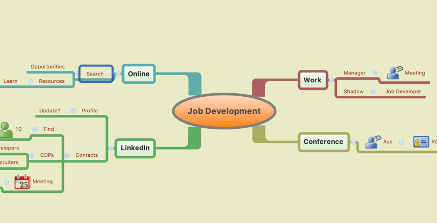

Mind mapping: A fun, visual tool for brainstorming and planning next steps. There are many tools available online to help guide clients through mind mapping (Xmind8 offers a free version). Watch Tony Buzan, the creator of mind maps, describe the tool: How to Mind Map with Tony Buzan.

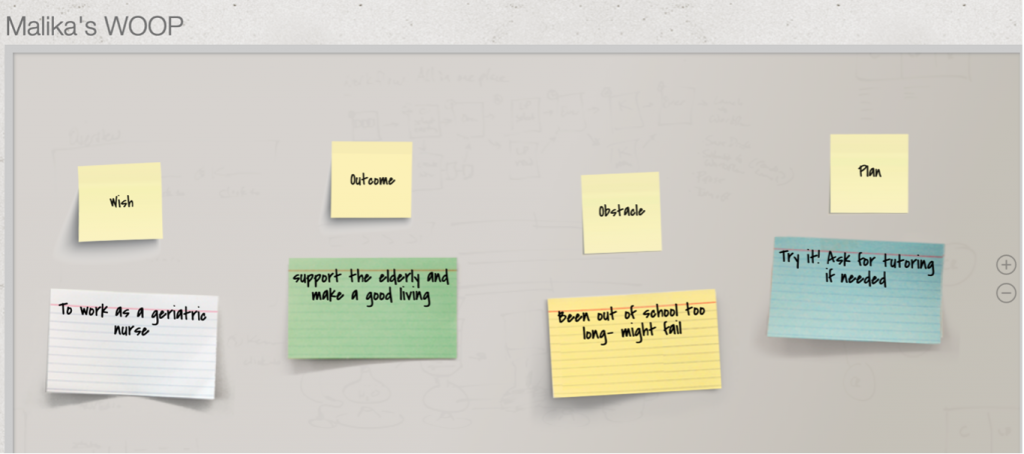

WOOP – Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan: WOOP is a “mental strategy” designed to assist people to reach their goals, based on 20 years of scientific research. Starting with a wish, this approach allows for building in a contingency plan to address potential obstacles. For example:

Karen Begemann, M.Ed., CCDP is a Career Consultant in private practice, Work Matters Consulting, and a contract instructor with Douglas College in the Career Development Practice Certificate Program. She has an MEd in Counselling, training in career development and 20 years’ experience. Begemann draws from her counselling background to seek new and ethical ways coach clients.

References

Ayoa. (2015, Jan 26). How to Mind Map with Tony Buzan. [Video]. YouTube. youtube.com/watch?v=u5Y4pIsXTV0

Bimrose, Jenny. (n.d.). Traditional theories, recent developments and critiques. warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/ngrf/effectiveguidance/improvingpractice/theory/traditional/#Learning%20theory%20of%20careers%20choice%20&%20counselling)

Magnusson, K. & Botelho, T. (2021, Jan 25-Feb 3) Working With-and Around-Emotions in Career

Helping [Conference Session] Cannexus21 Virtual. cannexus21.gtr.pathable.com/meetings/virtual/SqdyXtSQT6YG8iDt2

Psychology. (2018, March). Learning Theory of Career Counselling. bestpsychologyarticles.blogspot.com/2018/03/learning-theory-of-career-counseling.html?m=0)

Statistics Canada. (2020, Oct 20). Impacts on Mental Health. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/2020004/s3-eng.htm

Staunton, Tom. (2015, Apr 18). The Chaos Theory of Careers- Every Careers Advisor Should Know. runninginaforest.wordpress.com/2015/04/18/the-chaos-theory-of-careers-theories-every-careers-adviser-should-know/

TEDx Talks (2016, Nov 18). What Trauma Taught Me About Resilience, Charles Hunt, TEDXCharlotte. [Video]. YouTube. youtube.com/watch?v=3qELiw_1Ddg (at 7:44)

Truyens, Marc. (2019) Transition Theory – Nancy K Schlossberg 1984. marcr.net/marcr-for-career-professionals/career-theory/career-theories-and-theorists/transition-theory-nancy-k-schlossberg/

woopmylife woopmylife