What you measure matters … but your mindset matters more

October 6, 2021

The hybrid future: Shifting employment services to meet client needs

October 6, 2021The story of one community’s exploration of geographic solutions to geographic poverty

Anne Gloger

The Storefront was originally funded by the federal government as an innovative approach to providing employment services for people furthest away from the labour market. By creating this community-based, one-stop shop, The Storefront seamlessly brought together quality employment services and easily accessible wrap-around supports under one roof. The Storefront became a trusted place in the community that offered holistic services, thereby eliminating or reducing the need for jobseekers to navigate systems in order to have their needs addressed.

This was the early 2000s, when there was growing evidence that in Toronto, like in so many cities across Canada, poverty was becoming increasingly concentrated in specific communities. These communities, predominantly in the inner suburbs, were and are largely populated by people of colour, and are plagued by decades of underinvestment, poor transit and few options for decent work (United Way of Greater Toronto, 2004; 2011; Hulchanski, 2010; 2015).

Over the next two decades, both on-the-ground experience and research evidence began painting a picture of geographic poverty and yet, there were few geographic solutions to this rapidly increasing problem. Ultimately, social services were never going to be enough to reverse this alarming trend. Access to decent work is fundamental to geographic solutions to geographic poverty. The Storefront was well positioned to begin exploring innovative, community-centred approaches to workforce development to create that access.

Images provided by author.

Working in the context of a community ecosystem

What was unique about The Storefront’s approach to designing and operating a service hub was its emphasis on facilitating and stewarding inclusive processes, constantly listening, learning, iterating and fostering collective action. Surfacing local stories and ideas made it glaringly obvious that while the service hub effectively broke down barriers to service access, the community aspired to so much more.

Services help people overcome individual barriers to jobs. The people of East Scarborough identified that, in communities like theirs, so many barriers were not individual, but systemic. Services are important and necessary, but do little to shift the systems that for too long have acted to keep Black, Indigenous and people of colour from accessing opportunities to decent work.

Read more:

Employer-engaged workforce development: Strategies to address sector shock

What students want from employers to create safe, inclusive workplaces

3 ways to transform your organization by creating a culture of continuous learning

The Storefront was created as a “by the community, for the community” solution to service access. The Storefront’s role as facilitator and convenor has been variously called a network weaver, an integrator and a community backbone organization. Over time, by learning together with partners and community, it became clear that the implications of this role could go well beyond service delivery, and could make a significant contribution to improving economic inclusion in marginalized communities.

Systemic barriers need systemic solutions

A visionary funder, the George Cedric Metcalf Foundation, invested in the early research and development that The Storefront needed to understand the potential of being an integrator or community backbone organization in local economic inclusion.

Early insights from the Democracy Collaborative in Cleveland, Ohio helped to identify that in many marginalized communities, decent work did in fact exist: “Cities are increasingly turning to their ‘anchor’ institutions as drivers of economic development, harnessing the power of these major economic players to benefit the neighborhoods where they are rooted. This is especially true for cities that are struggling with widespread poverty and disinvestment.” (Wright et al., 2018)

Anchors are institutions that are “rooted in place” like hospitals, universities and, in the case of East Scarborough, the local zoo. Millions of dollars are spent and hundreds of jobs are created in these anchor institutions and yet, local people, especially people who are racialized and living in poverty, are rarely able to take advantage of these employment opportunities. In 2016, The Storefront, as part of the provincial poverty-reduction strategy, began to explore how workforce integration at a local level might make a difference.

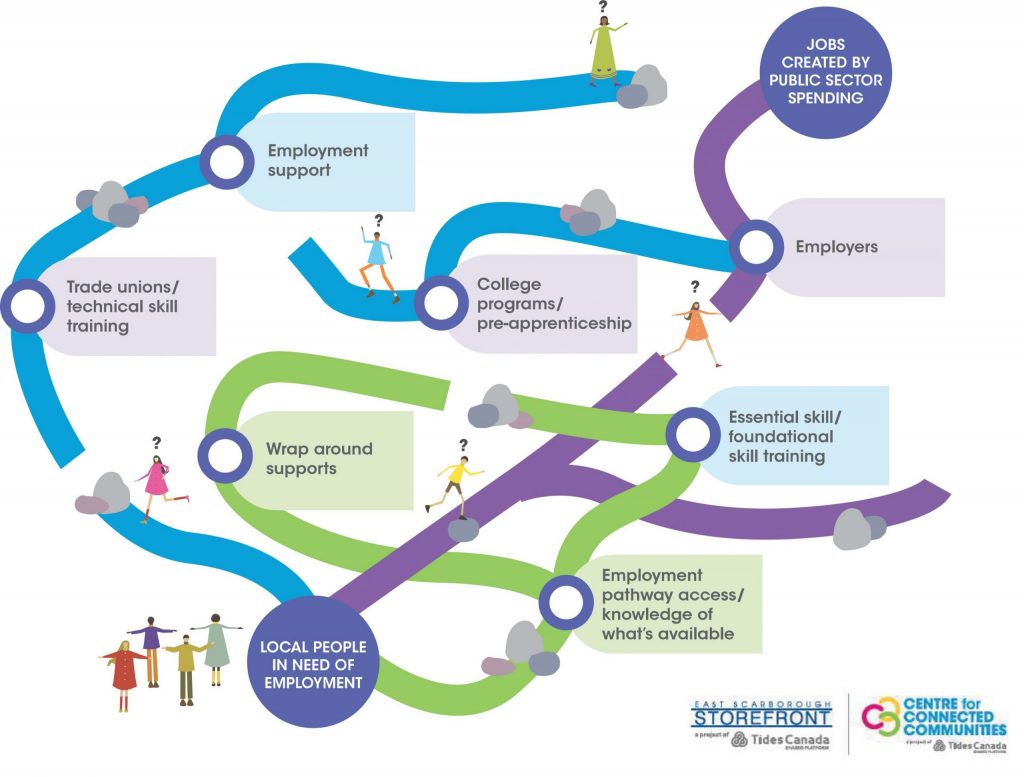

The Storefront’s role as an Employment Ontario service provider brought insights into just how programmatic, siloed and fragmented the workforce ecosystem was in East Scarborough. While there were excellent organizations doing excellent work, there was no unifying vision that would help address the personal, practical and systemic barriers that local people were facing accessing decent work.

East Scarborough Works: Place-based workforce development in action

Employment services are essential in helping people find, secure and keep employment. Our research found, however, that employment organizations are often frustrated by the complex dynamics of employer cultures, recruitment norms, and economic and regulatory environments that exist at the “demand” end of workforce development pathways.

The research further revealed that people furthest away from the labour market often feel that employment services are not for them. While there are certainly exceptions, by and large, employment organizations work with the people who walk through their doors or attend formalized events, leaving those who don’t further marginalized from the labour market.

And finally, without intentional integration, employment service providers often struggle to find the right wrap-around supports and the right training to help people furthest from the labour market prepare for and secure employment.

East Scarborough Works (ESW) was born out of The Storefront’s experience as a service hub integrator and from new learnings about the employment ecosystem. It is based on the recognition that even when the components of employment ecosystems exist in a community – jobseekers, social services, training organizations, employment organizations and employers – they are typically disconnected from one another. Local expertise, assets and resources are critical to creating effective local workforce development strategies, but leveraging them requires a new way of working.

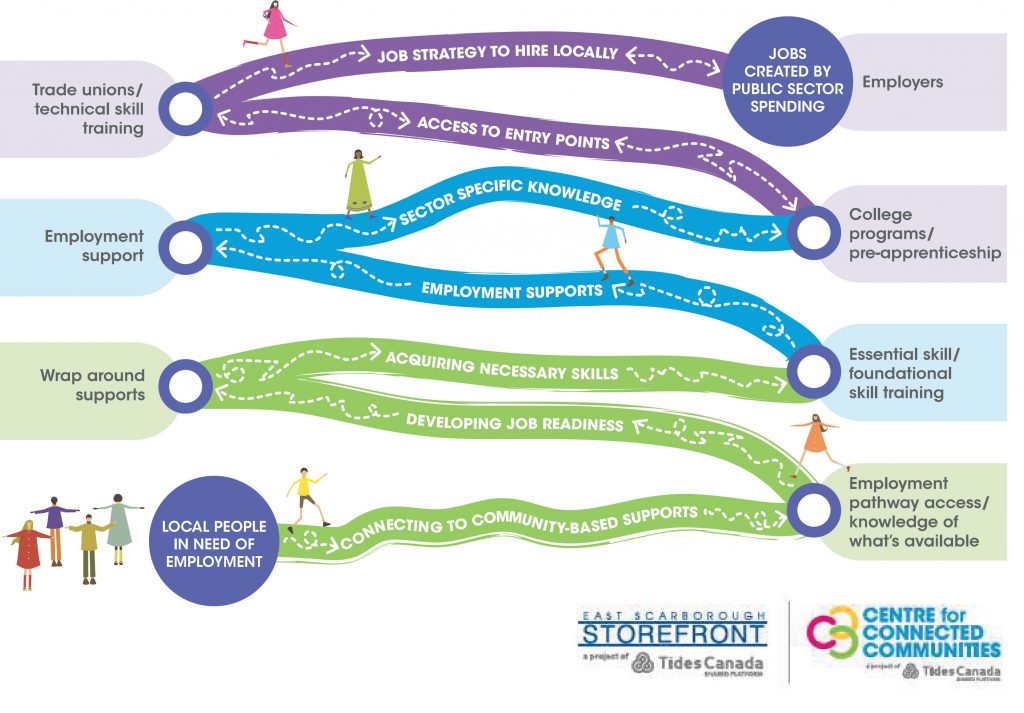

East Scarborough Works uses a Connected Community Approach (CCA) to cultivate a deep understanding among local people, organizations and networks about each other’s mandates, priorities and expertise. This understanding creates a foundation for multiple organizations to work together to ensure that local people have the best opportunity to prepare for jobs created by anchor institutions.

Early prototypes have shown promising employment outcomes: pre-pandemic results in hospitality saw 22 local people secure employment at a new event venue and a success rate of 70-80% in the social sector. The ultimate impact, however, is in changes in the system. To this end, we have seen:

- Increased transparency from anchor institutions about recruitment needs and processes

- Improved cross community/cross-sector communication

- Increased collaboration among Employment Ontario organizations

- Increased voice and involvement of grassroots groups in problem solving and outreach

- Improved overall understanding of the community as ecosystem and who plays what role in supporting people furthest from the labour market to secure decent work

Based on these early outcomes, The Storefront has begun working collectively with anchor institutions, service providers, trainers and jobseekers to design demand-led, supply-driven, network-managed workforce development pathways in construction, tourism and facilities maintenance.

Implications beyond East Scarborough

East Scarborough Works is one of the inaugural projects of Toronto’s innovative Workforce Funders Collaborative (TWFC). TWFC, Metcalf Foundation and other funders and policy-makers are helping to deepen our collective understanding of the potential of using the Connected Community Approach in place-based workforce development.

East Scarborough is not the only community where people furthest from the labour market are unable to access jobs created through large-scale local investment in anchor institutions. What is emerging in East Scarborough can be adopted and adapted to work in various contexts.

The model beyond East Scarborough is known as Connected Communities Work (CCW), which takes a whole-community approach to supporting people furthest from the labour market to prepare for and secure local employment. The Future of Good has identified CCW as one of the country’s most promising initiatives to move toward more equitable and sustainable cities post-pandemic.

The City of Toronto has adopted the model as a pilot in its new Community Benefits Framework. Together with the Centre for Connected Communities, the City is exploring how CCW can move the needle on equity hiring associated with large-scale development and anchor institutions in communities across the city.

Researchers have been pointing to increasing geographic concentration of poverty in Canadian cities for almost two decades now; there are, however, relatively few examples of successful geographically based strategies to address it. The Storefront’s service hub is one such example and its relatively new foray into local workforce development is poised to be another. And we need a lot more, because, as local residents, researchers and employment service organizations will tell you, geography does matter.

Anne Gloger is the founding Director at the East Scarborough Storefront and Principal at the Centre for Connected Communities. Gloger’s background includes early childhood education, social development and business. She has over three decades of experience co-designing impactful community projects and approaches including the Connected Community Approach for which she has received several awards including the Canadian Urban Institute David Crombie City Builders Award, the Jane Jacobs prize and the William P Hubbard Award for Race Relations.

Additional references

Bhatia, A., Heese-Boutin, C.-H. & Roy, M. (2020). Geography Matters. Metcalf Foundation. https://metcalffoundation.com/special-series/the-working-poor-three-perspectives/

Gloger, A. (2016). The Connected Community Approach: What it Is and Why it Matters. https://connectedcommunities.ca/C3-2017/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/CCA-What-it-is-and-why-it-matters.pdf

Mann, C. (2012). The Little Community That Could. East Scarborough Storefront. http://www.thestorefront.org/ourbook/index.html

Stapleton, J., Murphy, B. & Xing, Y. (2012). The “Working Poor” in the Toronto Region: Who they are, where they live, and how trends are changing. Metcalf Foundation. https://metcalffoundation.com/publication/the-working-poor-in-the-toronto-region-who-they-are-where-they-live-and-how-trends-are-changing/