Choose crisis before crisis chooses you

October 24, 2022

Yes, your employees are still burned out. Here’s what you can do about it

October 24, 2022The pandemic has set the stage for individuals to reflect on, embrace and overcome challenges related to their career goals

Geneviève Taylor, Kaspar Schattke and Ariane Sophie Marion-Jetten

What is a career action crisis?

An action crisis represents the internal conflict that arises when thinking about whether to continue with or to give up an important (career) goal, for which difficulties have been accumulating. This has important negative consequences, such as elevated distress and depression. It can also make failing one’s goal more likely and often leads to giving it up. Giving up career goals can be unsettling because they are usually identity-defining. However, what if going through an action crisis is exactly what Julian needs to realign his career with the life he really wants to live?

We do not know much about the potential positive long-term outcomes of career action crises. While it is certainly distressing, an action crisis can also represent a “golden opportunity.” It may provide an occasion to reflect on one’s career goals, to let go of the ones that no longer make us happy, and to help us find more motivating and meaningful goals. However, this depends on how we cope with our action crisis, which is precisely where career development professionals can help.

More from Careering

Three dimensions of career decision-making

From compassion fatigue to compassion satisfaction

Stress-management strategies from occupational therapy

Action crises through the lens of the Rubicon Model

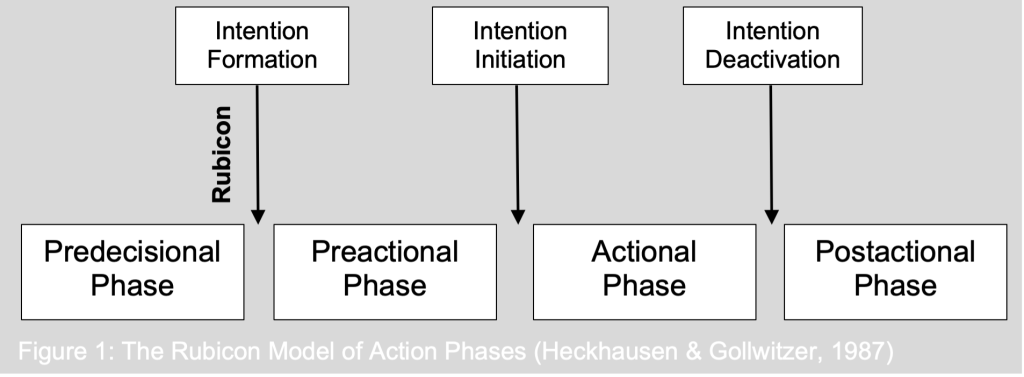

Career development professionals frequently meet clients who are experiencing a career action crisis, without using that terminology. The Rubicon Model of Action Phases helps us to understand why action crises are problematic by differentiating four phases of goal pursuit (see Figure 1).

In the predecisional phase, people deliberate about how desirable and feasible their different wishes are. Intending to put a wish into action turns it into a goal. At that point, we have “crossed the Rubicon,” as Julius Caesar literally did to conquer Rome. In the preactional and actional phases, people plan and execute their actions, respectively, while ignoring the pros and cons of their decision to focus on goal attainment. In the postactional phase, people reflect on their progress, or lack thereof.

In an action crisis, people start oscillating between the predecisional and preactional/actional phases, preventing them from effectively pursuing their goal because they question it instead of working on it. For example, Julian starts losing games and wonders whether to let go of his European ambitions.

“While it is certainly distressing, an action crisis can also represent a ‘golden opportunity.'”

How can career professionals use the Rubicon Model to help their clients cope with and learn from an action crisis? Our own research suggests that mindfulness is linked to a reduction in action crisis severity and can help individuals who are coping with an ongoing one. Thus, we propose three ways of turning career action crises into “golden opportunities.”

1. Reflecting on career goals and embracing action crises

A career action crisis offers the opportunity to readjust our priorities related to an overarching goal. We will have to “cross the Rubicon” again, either in deciding to keep and recommit to the initial goal, with necessary adjustments, or to abandon it and re-engage in another goal. One means to facilitate this challenge of embracing an unpleasant action crisis can be self-compassion, consisting of three components:

- Self-kindness – being caring toward oneself after failure

- Common humanity – recognizing our negative experiences as a part of being human

- Mindfulness – paying attention in an accepting, non-judgmental way to our thoughts, sensations and emotions, in the present moment

For example, we could help Julian become mindful of his anxiety and self-critical thoughts, be kind with himself for having experienced unanticipated obstacles such as losing games and help him recognize that this just makes him human. This way, we normalize experiencing an action crisis and allow our client to accept his negative thoughts and emotions without avoiding or being consumed by them.

2. To disengage or not to disengage? That is the question

After having reflected upon and embraced the action crisis as an opportunity, we can help the client explicitly explore whether they need to disengage from their goal. First, why did the person initially engage in their career goal? Was it because of external or internal pressure (controlled reasons), or because it was related to their values and interests (autonomous reasons)? A career goal chosen for mostly controlled reasons will be more likely to lead to action crises in the future, and to decrease goal progress and increase distress. If a person already has an action crisis for a controlled goal, it could be time to disengage and search for a more autonomous goal, one that is connected to their values/interests.

Second, we can support clients to consider the attainability and desirability of the goal. In Julian’s case, is getting into a European league still attainable and something worth investing in?

Finally, one has to evaluate the obstacles that triggered the action crisis. Are they surmountable? If it is a desirable, attainable and autonomous goal, is it worth continuing to work on getting over the obstacles? If so, then we can use tools such as WOOP, which helps us reflect on our Wish (goal), its desired Outcomes, internal Obstacles and create an action Plan to overcome the obstacles. If the goal is not desirable, attainable and autonomous, then we can help the client to disengage from it, cognitively, emotionally and behaviorally.

iStock

3. Re-engaging after an action crisis

After disengaging from a career goal, the challenge is to help the client re-engage in a more meaningful, feasible and fulfilling career goal that reflects their true passions, interests and core values. They can achieve this through various exercises that career counsellors use daily, such as interest inventories, value exploration, narratives and life space mapping.

Another complementary tool clients can use is a mindfulness practice to pay attention to how they feel when discussing certain goals: Do they feel tight in the chest or open and relaxed? This could help identify new areas for goal setting; however, it is important to explore the source of these feelings first, which could also stem from anxiety around uncertainty or considering a goal that is largely different from what they are used to, rather than because it is not the “right” goal for them.

Finally, since career goals are usually identity defining, another idea is to help clients re-engage in a related goal. For example, Julian could aim for a career as a trainer in a European club if his injuries do not allow him a career as a player at a high level.

Conclusion

An action crisis is an unpleasant experience, yet it also constitutes an opportunity for realigning life priorities with work goals. Using mindfulness and self-compassion can help to embrace an action crisis in lieu of fighting it. It can help to figure out which “Rubicon to cross”: the one that reaffirms the initial goal or the one that disengages and re-engages in a new career goal, while applying the wisdom that the action crisis experience has bestowed upon us. Without the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us would have never had this opportunity.

Geneviève Taylor, PhD, is a professor in career counselling at Université du Québec à Montréal. She obtained a Master’s degree in Human Resource Management from the London School of Economics and a doctorate in clinical psychology from McGill University. Her current research focuses on the role of mindfulness and self-compassion in career-related goal pursuit and other motivational processes.

Originating from Berlin, Kaspar Schattke obtained a doctorate from the Technical University of Munich and is now an Associate Professor at Université du Québec à Montréal in work and organisational psychology. Dr. Schattke is also a certified management trainer and consultant specialized on leadership and motivation. His current research interests focus on goal disengagement, greenwashing and work motivation.

Ariane Sophie Marion-Jetten, PhD, is a postdoctoral researcher in the Faculty of Psychology and Movement Science at Universität Hamburg, Germany. Her research focuses on the role of mindfulness and implicit and explicit motives congruence for self-regulation and goal pursuit (career and other types).