Anti-racism from the inside out: Challenging white supremacy in the workplace

How the Kootenay Career Development Society is working to confront institutionalized racism within its own walls

Malorie Moore

In her 2017 book, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge states: “The perverse thing about our current racial structure is that it has always fallen on the shoulders of those at the bottom to change it. Yet racism is a white problem. It reveals the anxieties, hypocrisies and double standards of whiteness. It is a problem in the psyche of whiteness that white people must take responsibility to solve. You can only do so much from the outside.”

In her 2017 book, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge states: “The perverse thing about our current racial structure is that it has always fallen on the shoulders of those at the bottom to change it. Yet racism is a white problem. It reveals the anxieties, hypocrisies and double standards of whiteness. It is a problem in the psyche of whiteness that white people must take responsibility to solve. You can only do so much from the outside.”

Reni Eddo-Lodge is correct; the responsibility to challenge white supremacy within organizational structures lies with folks who have the power to make these changes. This refers to people in management and executive-level positions, particularly if they are white. It is with this statement in mind that I have written this article, and my hope is that it might inspire other organizations with predominantly white management and board structures to take action. Please note that I am not an expert, and as an organization we are at the very beginning of our anti-racism journey. This article is not a how-to guide by any means, but rather a transparent account of how our organization has started to challenge institutionalized racism in the workplace.

A note on white supremacy

Please note that for the purposes of this article, any references to the term white supremacy refers to a complex set of societal structures, systems and attitudes. In her 2020 book Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad describes white supremacy in the following way: “White supremacy is a racist ideology that is based upon the belief that white people are superior in many ways to people of other races and that therefore, white people should be dominant over other races. White supremacy is not just an attitude or a way of thinking. It also extends to how systems and institutions are structured to uphold this white dominance … White supremacy is far from fringe. In white-centred societies and communities, it is the dominant paradigm that forms the foundation from which norms, rules and laws are created.”

Who are we?

The Kootenay Career Development Society is a non-profit organization that operates across multiple rural communities in the East Kootenays in BC. We have approximately 60 staff, and our staff, board and management teams are predominantly white. While we have been engaged in a number of practices that emphasize a commitment to diversity and inclusion for a number of years, both in our service delivery and recruitment, it was not until the spring of 2020 that we took a step back to critically evaluate our organizational stance on the topic of anti-racism.

How did our process begin?

This process began at the initiative of a manager who is a person of colour. While I applaud my team for their openness to listen and subsequently act, if we conceptualize racism as a white problem, this work could, and should, have been undertaken sooner by a white manager. I mention this to highlight the fact that the labour of anti-racism work is often shouldered by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour) folks, as well as to encourage other white people reading this to take action sooner. One of the biggest challenges in dismantling racism in the workplace may be taking that first step, and as well-intending white people, we can’t allow ourselves to hesitate to take action for fear of not having all the answers.

More from Careering

To help others reach their career goals, use your privilege for good

Diversity in corporate sponsorship critical to help talent rise

Working with employers to support non-traditional hiring

Our first steps

Our first step was to create an Anti-Racism Working Group. The purpose of this group was to identify and take action on a number of anti-racism strategies in a timely manner. In order to meet this goal, we needed to meet often (2-4 times per month) and include managerial staff with decision-making capacity. From the beginning, we had members of our executive management team, including our Executive Director, involved as active participants in this working group. These meetings led us to undertake several projects.

“… we can’t allow ourselves to hesitate to take action for fear of not having all the answers.”

With input from our entire staff team, we created a statement of solidarity to voice support for the Black Lives Matter movement. We also crafted an Indigenous land acknowledgement to include in our email communications and share at the beginning of staff meetings and other gatherings. Both the statement of solidarity and the Indigenous land acknowledgement can be found on our webpage and were shared on social media. Anticipating some pushback from staff or community members, we brainstormed ways to respond to defensive or racist comments. However, we received far less pushback that we had originally anticipated, and most of the feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

Regarding service delivery, we recognized the need to involve front-line staff in ongoing education around topics of racism and white supremacy. We shared resources with staff and encouraged professional development through courses such as Indigenous Canada and in-house training on cultural competency and safety. We allotted work time for an employee book club, where staff read or listened to the Thomas King Massey lecture series, “The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative,” and met on a bi-weekly basis to discuss their learnings.

Most notably, we organized anti-racism training through the Alberta-based group Future Ancestors. While KCDS provides annual diversity and inclusion training to staff, the anti-racism training was different. It used language that encouraged white people to take active responsibility for their complicity in a society that is built on a foundation of anti-Black racism and colonialism. We are taking time each month as a team to review this training and explore how we can incorporate our learning in our roles as service providers. Some recent conversations have focused on the importance of reflecting on our own biases throughout the service delivery process and making an effort to be aware of oppressive language and choose our words with care.

As a management team, we attended our own anti-racist training, where we had the opportunity to have our statement of solidarity dissected and examined. We were encouraged to be specific as to how we were going to live up to the ideas expressed in this statement. We responded to this by ensuring that our strategic plan included a goal for more diverse hiring, as well as better serving clients that are under-represented in our area. We are still in the process of refining our strategic plan and I acknowledge that we have more work to do in defining these goals further and ensuring that we are avoiding vague or coded language.

Finally, we acknowledged that as a predominantly white management team, we do not have the tools or resources to make all the “right” changes. We acknowledged that to be effective, we needed help. To this end, we made the decision to hire an external consultant to support us in identifying the areas we need to change in order to evolve into a more anti-racist organization.

And there you have it; the early stages that we as an organization are taking to challenge white supremacy in our workplace. We have made mistakes (and will continue to do so), but I am grateful to say that the fear of making mistakes has not stopped us from trying to change for the better.

Malorie Moore is a Registered Social Worker employed with the Kootenay Career Development Society. Here, she draws upon her background in mental health and working with marginalized populations to support the clinical development of the organization and front-line staff. Moore loves living in the Kootenays, where she spends her free time canoeing, climbing and playing in the mountains.

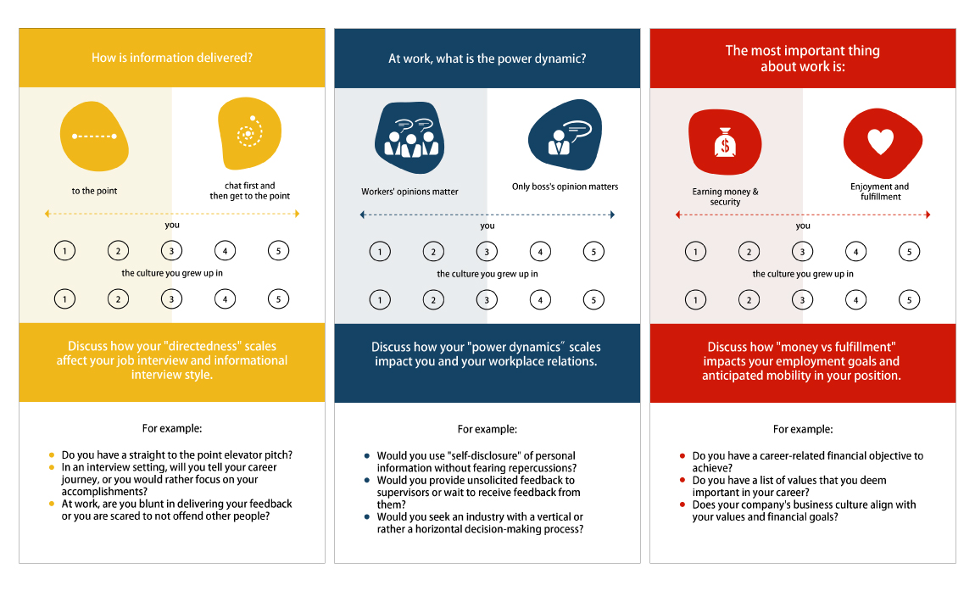

Career development tailored to international students is a necessary component of a broader institutional educational strategy that involves many stakeholders. However, barriers hamper co-operation between organizations that offer career and personal development services to international students (e.g. higher-education institutions, non-profit and grassroots organizations). Drawing from my experience as a career development facilitator in a grassroots organization called Empower International Students, I discuss the importance of identity exploration and I present an innovative tool that can be used by career practitioners to help international students and newcomers “find their voice” in their career development.

Career development tailored to international students is a necessary component of a broader institutional educational strategy that involves many stakeholders. However, barriers hamper co-operation between organizations that offer career and personal development services to international students (e.g. higher-education institutions, non-profit and grassroots organizations). Drawing from my experience as a career development facilitator in a grassroots organization called Empower International Students, I discuss the importance of identity exploration and I present an innovative tool that can be used by career practitioners to help international students and newcomers “find their voice” in their career development.

Islam is one of the fastest-growing religions in the world, and within Canada, the Muslim population is rapidly expanding. According to the Pew Research Center (2011), Muslims account for 3.2% of the Canadian population, and their global population is expected to increase by 35% by the year 2030. As the Muslim population increases in Canada, there is a growing need for culturally responsive counselling services that consider its values and challenges (Qasqas & Jerry, 2014). Such challenges include the experience of trauma that some Muslim immigrants carry from war-affected countries, as well as the effects of Islamophobia that many immigrant and Canadian-born Muslims experience as a marginalized minority group in a Western country (Qasqas & Jerry, 2014; Rothman & Coyle, 2018, 2020). This is especially important in the post-9/11 world and due to repercussions from the “Trump era” in the United States, during which negative and inaccurate media representations of Islam have led to the further marginalization of Muslims globally (Qasqas & Jerry, 2014).

Islam is one of the fastest-growing religions in the world, and within Canada, the Muslim population is rapidly expanding. According to the Pew Research Center (2011), Muslims account for 3.2% of the Canadian population, and their global population is expected to increase by 35% by the year 2030. As the Muslim population increases in Canada, there is a growing need for culturally responsive counselling services that consider its values and challenges (Qasqas & Jerry, 2014). Such challenges include the experience of trauma that some Muslim immigrants carry from war-affected countries, as well as the effects of Islamophobia that many immigrant and Canadian-born Muslims experience as a marginalized minority group in a Western country (Qasqas & Jerry, 2014; Rothman & Coyle, 2018, 2020). This is especially important in the post-9/11 world and due to repercussions from the “Trump era” in the United States, during which negative and inaccurate media representations of Islam have led to the further marginalization of Muslims globally (Qasqas & Jerry, 2014).

Being referred to as an ally is a gift. It is a privilege and an honour, but also humbling and daunting. Once allyship is recognized, the ally carries the responsibility to walk the talk and to never assume allyship is like clothing that one can remove at will – just as those who are and have been oppressed cannot remove the object of their oppression. Allyship is a journey, not a destination. It comprises critical reflexivity, cultural awareness, cultural safety, cultural agility and cultural competencies in understanding health, wellness and resilience of Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) individuals and groups who face oppression and discrimination.

Being referred to as an ally is a gift. It is a privilege and an honour, but also humbling and daunting. Once allyship is recognized, the ally carries the responsibility to walk the talk and to never assume allyship is like clothing that one can remove at will – just as those who are and have been oppressed cannot remove the object of their oppression. Allyship is a journey, not a destination. It comprises critical reflexivity, cultural awareness, cultural safety, cultural agility and cultural competencies in understanding health, wellness and resilience of Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) individuals and groups who face oppression and discrimination.

I never knew what I wanted to be when I grew up. In fact, I was quite jealous of those who did –my high school classmates who were so certain of their future career, it seemed like nothing would get in the way of their plans. I never had that.

I never knew what I wanted to be when I grew up. In fact, I was quite jealous of those who did –my high school classmates who were so certain of their future career, it seemed like nothing would get in the way of their plans. I never had that.

Canada geese walked freely in this women’s prison grounds; inmates and volunteers did not. It looked foreboding at first. Large circles of barbed wire ringed the facility. An escort took us through security, guards carried lots of keys. The women were dressed in identical, khaki prison clothes. There was a 10-minute window each hour to move locations – from work or a housing unit to our classroom in the chapel complex. Hard to keep hope alive in this setting, you might think. And yet, that is what the prison staff tried to do, and that is what the career class series I taught in a California prison was all about. What keeps hope alive if you are involved in the criminal justice system? In this article, we explore how those of us in the career field can address this question.

Canada geese walked freely in this women’s prison grounds; inmates and volunteers did not. It looked foreboding at first. Large circles of barbed wire ringed the facility. An escort took us through security, guards carried lots of keys. The women were dressed in identical, khaki prison clothes. There was a 10-minute window each hour to move locations – from work or a housing unit to our classroom in the chapel complex. Hard to keep hope alive in this setting, you might think. And yet, that is what the prison staff tried to do, and that is what the career class series I taught in a California prison was all about. What keeps hope alive if you are involved in the criminal justice system? In this article, we explore how those of us in the career field can address this question.

With the rapidly changing workplace, it’s more important than ever to be confident in using technology. Technology aids us in almost every aspect of life, as we have seen during COVID-19 with the shift to online work. However, mature workers struggling with technological literacy continue to feel left behind. As technology innovates at an exponential pace, many older adults view learning new technologies as an insurmountable challenge. Career development programs can build competencies and confidence by providing practice in low-stress learning environments and ensuring that mature students are better prepared to use technology during the hiring process and within the workplace. Integrating new and up-to-date technologies within and throughout a career development program provides older adults the opportunity to gain confidence in using technology while increasing their employability and developing new skills.

With the rapidly changing workplace, it’s more important than ever to be confident in using technology. Technology aids us in almost every aspect of life, as we have seen during COVID-19 with the shift to online work. However, mature workers struggling with technological literacy continue to feel left behind. As technology innovates at an exponential pace, many older adults view learning new technologies as an insurmountable challenge. Career development programs can build competencies and confidence by providing practice in low-stress learning environments and ensuring that mature students are better prepared to use technology during the hiring process and within the workplace. Integrating new and up-to-date technologies within and throughout a career development program provides older adults the opportunity to gain confidence in using technology while increasing their employability and developing new skills.

There is a commercial out about

There is a commercial out about

Canada’s career development sector enjoys an enviable international reputation. While attending the 2019 International Centre for Career Development and Public Policy (ICCDPP)

Canada’s career development sector enjoys an enviable international reputation. While attending the 2019 International Centre for Career Development and Public Policy (ICCDPP)

With the movement for social justice in full swing, many workplaces feel compelled to do something, anything, to demonstrate that they are diverse and inclusive and support the notion that #BlackLivesMatter. With each new Chief Diversity Officer job posting, companies in all sectors are sending messages to their stakeholders and staff that their organizations need fixing – and that they did not truly care about diversity and inclusion or anti-Black racism until now.

With the movement for social justice in full swing, many workplaces feel compelled to do something, anything, to demonstrate that they are diverse and inclusive and support the notion that #BlackLivesMatter. With each new Chief Diversity Officer job posting, companies in all sectors are sending messages to their stakeholders and staff that their organizations need fixing – and that they did not truly care about diversity and inclusion or anti-Black racism until now.