Winning in an open relationship: A partnership in higher education with industry

By Sonja Johnston

The “skills gap” (e.g., Lapointe & Turner, 2020; Mishra et al., 2019; RBC, 2019), or the misalignment of graduate capability with employer expectations, comes back to higher education to renovate education outcomes to align to industry desires for skill competency. However, this moving target of desirable skills in a tumultuous landscape for employment makes hitting the target nearly impossible. The literature in this space has been growing for decades, but the COVID-19 pandemic brought the challenge centre stage, as economic recovery will be directly affected by the ability of the workforce to adapt and innovate.

Solutions to close the gap have focused on supporting students to acquire skills as directed by industry insights and hiring needs. What if the narrative was reframed to explore collaborative and generative learning experiences that are co-created by industry partners and soon-to-be graduates?

One such example features the open learning partnership with e-commerce software leader Shopify (Shopify Open Learning, n.d.). This multinational, publicly traded, Canadian firm “is a leading provider of essential internet infrastructure for commerce, offering trusted tools to start, grow, market, and manage a retail business of any size” (Shopify Company Info, n.d.). Shopify’s open learning partnership allows higher-education programs to implement authentic learning experiences in curriculum by allowing students to create fully functional Shopify stores. Approved courses can utilize access to rewarding Shopify-based activities and students can earn digital badges to recognize their achievements in addition to the course credit.

During the pandemic, businesses were affected by health restrictions and forced to consider how they engaged with customers. As the Shopify platform evolved, students were able to learn about business demands and pivots in real time. Graduates enter the workplace with an authentic and experiential view of store design and strategic customer experience considerations. Shopify gains client insights from the students and an educated base of graduates ready to hit the ground running as entrepreneurs and employees.

This open (platform) relationship is an exchange of insight, expertise, current operations, feedback and authentic learning with no financial obligation to higher education. This iterative feedback loop functions differently than industry just providing insights on skills that are desired. The use of platforms provides authentic and experiential learning with the value-added opportunity for micro credentialling (i.e. digital badges). The win for all involved stakeholders is visible, and can pivot as the environment requires. The invitation for industry leaders to consider open relationships with higher education is on the table for the taking!

Disclaimer: I am a graduate student in educational research examining models for graduate workplace readiness. As a post-secondary instructor, I use this open platform in an entrepreneurship course. I am not compensated in any way from Shopify. I wish to acknowledge credit for the pioneering of this Open Learning Platform to Pam Bovey Armstrong and Polina Buchan at St. Lawrence College in Ontario, Canada.

Sonja Johnston is a collaborative, multidisciplinary scholar with nearly a decade of experience in curriculum design and instruction in multiple post-secondary institutions. She is currently a PhD student in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary, specializing in Learning Sciences. Sonja’s research focuses on higher education and workplace readiness.

References

Lapointe, S., & Turner, J. (2020). Leveraging the skills of social sciences and humanities graduates. Skills Next 2020. https://fsc-ccf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UniversityGraduateSkillsGap-PPF-JAN2020-EN-FINAL.pdf

Mishra, P. T., Mishra, A., & Chowhan, S. S. (2019). Role of higher education in bridging the skill gap. Universal Journal of Management, 7(4), 134-139. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujm.2019.070402

RBC. (2019, May). Bridging the gap: What Canadians told us about the skills revolution [report]. RBC Thought Leadership. https://www.rbc.com/dms/enterprise/futurelaunch/_assets-custom/pdf/RBC-19-002-SolutionsWanted-04172019-Digital.pdf

Shopify. (n.d.). Company Info. https://news.shopify.com/company-info

Shopify. (n.d.). Open Learning. https://www.shopify.ca/open-learning

Skills don’t last forever, but many of our current models for skills development assume they do. As the need for skills changes alongside rapid technological advancements and demographic shifts, employers will need to consider how to keep their employees’ skills fresh – and our learning systems must adapt as well. This is particularly true when it comes to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that support millions of jobs. But can they do it?

Skills don’t last forever, but many of our current models for skills development assume they do. As the need for skills changes alongside rapid technological advancements and demographic shifts, employers will need to consider how to keep their employees’ skills fresh – and our learning systems must adapt as well. This is particularly true when it comes to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that support millions of jobs. But can they do it?

Overqualification is a common and well-known problem for the immigrant workforce. But the pandemic shed a different light on the issue: the products and services that we consider essential are also provided by immigrants whose talent potential is underutilized.

Overqualification is a common and well-known problem for the immigrant workforce. But the pandemic shed a different light on the issue: the products and services that we consider essential are also provided by immigrants whose talent potential is underutilized.

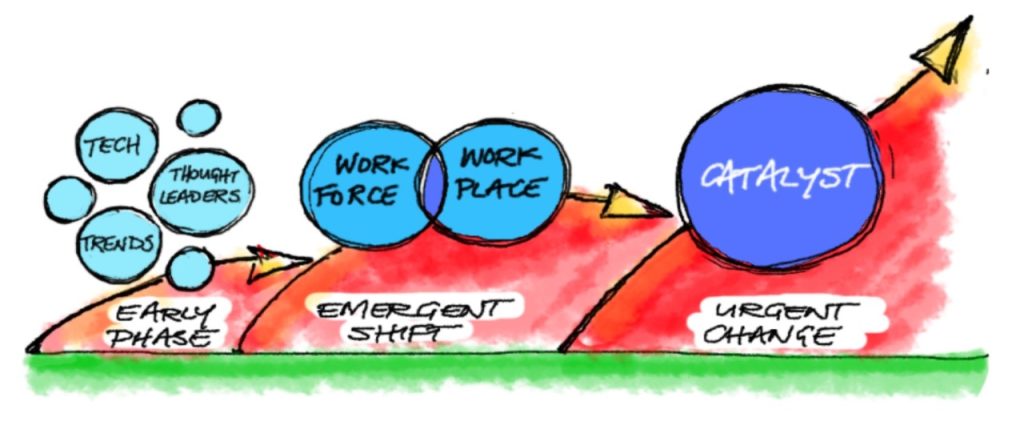

It’s an exciting time in Canada’s career development sector. Individual actors, organizations and projects are coming together. Awareness, expertise and commitment are coalescing. Focus is shifting from isolated activities to ambitious initiatives that emphasize co-ordination, amplify impact and prepare the sector for what comes next: a catalyst that ignites revolutionary change.

It’s an exciting time in Canada’s career development sector. Individual actors, organizations and projects are coming together. Awareness, expertise and commitment are coalescing. Focus is shifting from isolated activities to ambitious initiatives that emphasize co-ordination, amplify impact and prepare the sector for what comes next: a catalyst that ignites revolutionary change.

Dialogue and storytelling: Challenge Factory and CERIC are collaborating on a new

Dialogue and storytelling: Challenge Factory and CERIC are collaborating on a new

In my line of work, I am constantly helping students navigate major transitions from academics to the workforce. It is easy for me to look back now and understand how every step, failure and win helped me climb my career ladder. However, for a new graduate, the first step can seem like a hurdle – especially for a student with a disability.

In my line of work, I am constantly helping students navigate major transitions from academics to the workforce. It is easy for me to look back now and understand how every step, failure and win helped me climb my career ladder. However, for a new graduate, the first step can seem like a hurdle – especially for a student with a disability.

I recently spoke with an Elder from my community. He told me that the Creator is there to guide those who will listen and then he taught me about the Medicine Wheel. I do not have much experience with learning from an Elder, metaphorically sitting at their feet and trying to absorb truths handed down through each generation. I often wonder what that would have been like, if things had been different.

I recently spoke with an Elder from my community. He told me that the Creator is there to guide those who will listen and then he taught me about the Medicine Wheel. I do not have much experience with learning from an Elder, metaphorically sitting at their feet and trying to absorb truths handed down through each generation. I often wonder what that would have been like, if things had been different.

As we emerge from the pandemic and move toward the future of work, we cannot forget the systemic issues that were finally highlighted during the pandemic. The systemic issues affecting Black people in Canada are centred around the lack of access and sustainability in education, employment and health care for this community.

As we emerge from the pandemic and move toward the future of work, we cannot forget the systemic issues that were finally highlighted during the pandemic. The systemic issues affecting Black people in Canada are centred around the lack of access and sustainability in education, employment and health care for this community.