Pandemic prompts mindset paradigm shift around ‘return to work’

The accommodations to support workers after an illness or injury are often best practices for all employees

Tracey Kibble

In 2021, the phrase “return to work” has taken on a new meaning.

Before the pandemic, this phrase described and contextualized a worker’s reintegration into their place of employment following recovery from an accident, illness or injury. Workplaces, insurers and compensation boards had identified strategies to address the protocols of supporting workers to return to their work environments with potential modifications, accommodations and supports.

Before the pandemic, this phrase described and contextualized a worker’s reintegration into their place of employment following recovery from an accident, illness or injury. Workplaces, insurers and compensation boards had identified strategies to address the protocols of supporting workers to return to their work environments with potential modifications, accommodations and supports.

Vocational rehabilitation professionals were acutely aware of the inherent challenges associated with the return-to-work process. Research strongly confirmed the reality that many workers perceived or experienced discrimination, prejudice and decreased social value in the context of being identified as an injured or ill worker. As noted by Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, “Many individuals report being treated differently (and) stigmatized” upon re-entry to the workforce. Stigma for returning employees was often more significant for those who had been away from work recovering from acute or episodic mental health difficulties or other invisible conditions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a paradigm shift in mindsets around the phrase “return to work.” Over time, language, policies, legislation and societal perspectives change. What was previously acceptable and commonplace becomes obsolete, inappropriate, offensive or even illegal as cultural norms and practices are reconstructed. Thomas Kuhn’s 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, was transformative in coining the concept of “paradigm shift” – defined as an important change that happens when the usual way of thinking about or doing something is replaced by a new and different way. These epic mindset shifts occur perhaps once in a generation – for instance, the Great Depression or the 1969 moon landing. This global pandemic has created a paradigm shift that has affected all aspects of our society, including our mindset about how, when and where we work.

Read more

Social mentalities: A new approach to career mindsets

Maintaining a career mindset during times of change

Overcoming limiting beliefs can help clients move forward in their job search

Now, “return to work” has much broader connotations. Many people who began remote work during the pandemic face a return to in-person work for the first time since March 2020. The commonalities between the previous approaches for “return to work” in a traditional vocational rehabilitation context and the new normal being navigated by employers and employees may bring about a more thoughtful and adaptable landscape in the world of work.

Long before this pandemic, in 2011, the Government of Canada outlined key recommendations for what was traditionally called “return-to-work” planning, which included the following:

- The workplace has a strong commitment to health and safety, which is demonstrated by the workplace parties.

- The employer makes an offer of modified work (that is, work accommodation) to injured and ill workers so that they can return in a safe and timely manner to work activities that are suitable for their abilities.

- Return-to-work planners ensure that their plans support returning workers.

- Managers are trained in work disability prevention and included in return-to-work planning.

- The employer makes a timely and considerate contact with injured and ill workers.

- Someone has the responsibility to co-ordinate an employee’s return to work.

- With the worker’s consent, employers and health care providers communicate with each other about workplace demands as needed.

Previously, it was not uncommon for these return-to-work processes to be wrought with challenging negotiations and complex planning activities. As vocational rehabilitation professionals, we were frequently gatekeepers and co-ordinators in these systems, supporting both workers and employers to facilitate a successful return to work. However, over the past 18 months, discussions around health (both physical and psychological) and the workplace have become increasingly mainstream.

The pandemic and resulting changes and restrictions in our communities and workplaces have significantly negatively impacted many individuals’ well-being. Over 1.7 million Canadians have been diagnosed with COVID. Often the accommodations (whether addressing physical accessibility, the benefits of remote work, ergonomics, communication of medical information, modified scheduling, modification of tasks, job carving) that were previously recommended for returning workers following an accident, injury or illness are in fact best practices that could potentially benefit all employees. We already knew this.

In October 2021, the Canadian government recommended protocols for employers’ return-to-work practices that include open communication about policies and procedures, and encouragement for employees to take care of their physical and mental health. The Chartered Professional Accountants’ association has released guidelines highlighting workplace safety, employee rights, accommodations for medical conditions and flexible employment terms with the realization that employers need to acknowledge individual situations, manage expectations and focus on the immediate realities in return-to-work practices.

There are numerous parallels between the 2011 guidelines and the 2021 recommendations. What was previously specific to returning workers following an injury, illness or accident has, in many ways, become universal best practice in all employment settings, as employers have begun to re-group. A simple online search of the phrase “return to work” no longer yields results relating to ill or injured workers; instead, the process of “return to work” has become a commonplace phenomenon across all industries and work environments.

A mindset shift?

Will this new normal facilitate a more understanding and flexible world of work? Will many seemingly previously insurmountable obstacles shift to create more supportive work environments? Just maybe one positive outcome of the COVID-19 global pandemic has been a blurring of the boundaries between work and health, and a greater appreciation of our wellness – both physical and psychological. Time will tell if an acknowledged global need for more individualized expectations in the workplace will enable a conceptual mindset shift toward workplace practices that will benefit all and, as a result, reduce stigma for those who are re-entering the workforce after a non-COVID related absence.

Tracey Kibble, MEd (CRDS), RRP, RTWDM, CVRP, has been employed in the realm of social services, health care, education and return to work for the past 30 years. She is currently a Vocational Rehabilitation Services Manager with Metrics Vocational Services, a national provider of diverse and comprehensive vocational rehabilitation services across Canada. She is also the current president of the Vocational Rehabilitation Association (VRA) of Canada.

Research on prevailing success habits tells us that conversations are a fundamental

Research on prevailing success habits tells us that conversations are a fundamental

Lindsay Purchase

Lindsay Purchase

Randell Adjei is an entrepreneur, speaker and spoken word practitioner who uses his gifts to empower the message of alchemy. He was recently appointed

Randell Adjei is an entrepreneur, speaker and spoken word practitioner who uses his gifts to empower the message of alchemy. He was recently appointed

What was your first memory of a conversation you had as a child about education and the relationship to work? How old were you? Was it with parents, grandparents, a favourite aunt or uncle?

What was your first memory of a conversation you had as a child about education and the relationship to work? How old were you? Was it with parents, grandparents, a favourite aunt or uncle?

Sector shocks such as the impact of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry are nothing new and will continue to happen in the future. They can affect employment opportunities for jobseekers and the ability of employers to retain experienced workers as the industry navigates the novel impact of a shock. Within this context, workforce intermediaries like the Hospitality Workers Training Centre (HWTC) will have to change how we look at workforce development strategies that aim to support workers and help employers manage and recover from sector shocks.

Sector shocks such as the impact of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry are nothing new and will continue to happen in the future. They can affect employment opportunities for jobseekers and the ability of employers to retain experienced workers as the industry navigates the novel impact of a shock. Within this context, workforce intermediaries like the Hospitality Workers Training Centre (HWTC) will have to change how we look at workforce development strategies that aim to support workers and help employers manage and recover from sector shocks.

Like many other businesses, ACCES Employment had to respond quickly to the sudden and significant impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, the employment services sector overall moved swiftly to adjust years of honed service delivery practices to align with public health restrictions and safety protocols.

Like many other businesses, ACCES Employment had to respond quickly to the sudden and significant impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, the employment services sector overall moved swiftly to adjust years of honed service delivery practices to align with public health restrictions and safety protocols.

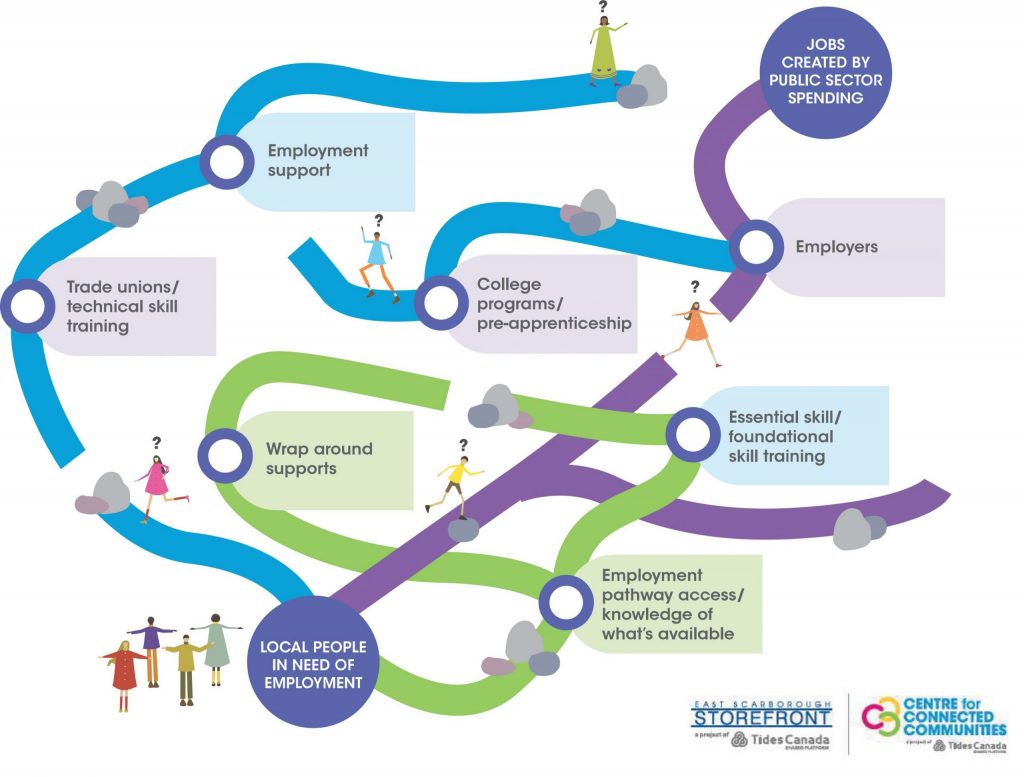

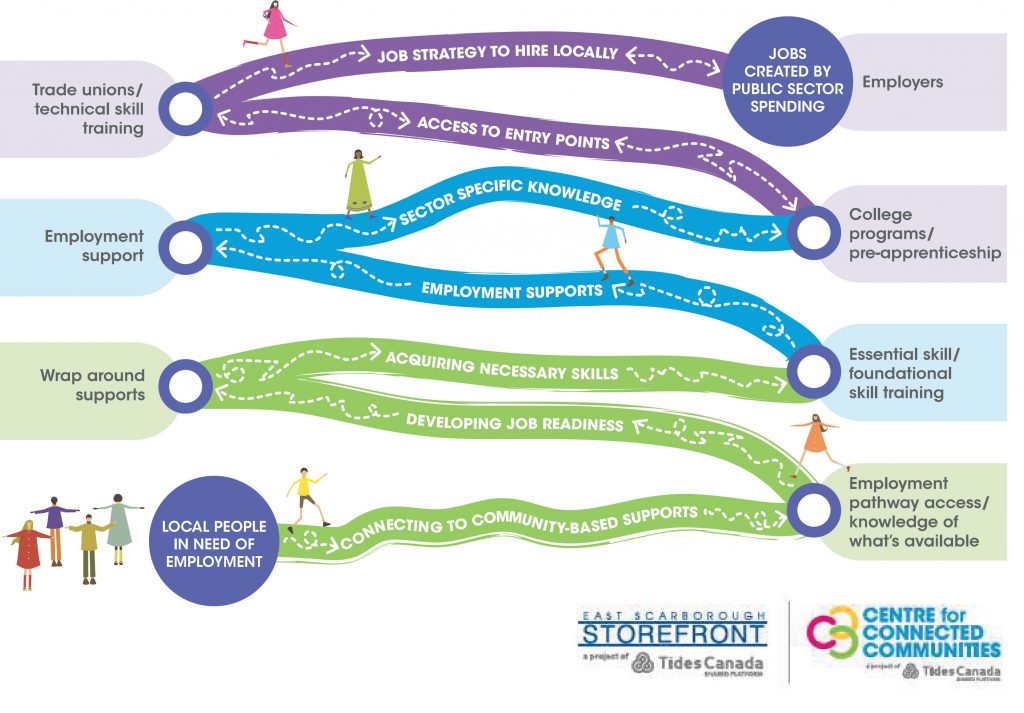

It was lack of services in the inner suburban community of East Scarborough, ON that prompted the design and development of a new kind of organization. The

It was lack of services in the inner suburban community of East Scarborough, ON that prompted the design and development of a new kind of organization. The

Equity, diversity, inclusion and accessibility (EDIA) have been major buzzwords in the labour market in the past 18 months. But it goes beyond language. The onset of a global pandemic has

Equity, diversity, inclusion and accessibility (EDIA) have been major buzzwords in the labour market in the past 18 months. But it goes beyond language. The onset of a global pandemic has

Over the past 30 years, and counting, career development professionals (CDPs), their managers and employers, along with various funders, have hotly debated the data that demonstrate the need for services and how to best evaluate the success of various interventions.

Over the past 30 years, and counting, career development professionals (CDPs), their managers and employers, along with various funders, have hotly debated the data that demonstrate the need for services and how to best evaluate the success of various interventions. Within the sector’s logic model, our ultimate outcome (i.e. what would happen if every other outcome was achieved) is to have Canadians manage learning and work to both build the lives they want and to contribute to a thriving and inclusive economy. This is a lofty goal, but it serves as an important north star, shaping the mindset we need to move forward.

Within the sector’s logic model, our ultimate outcome (i.e. what would happen if every other outcome was achieved) is to have Canadians manage learning and work to both build the lives they want and to contribute to a thriving and inclusive economy. This is a lofty goal, but it serves as an important north star, shaping the mindset we need to move forward.