October 6, 2021

- All

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

- 2019

- 2019

- 2020

- 2020

- 2021

- 2021

- 2021

- 2022

- 2022

- 2022

- 2023

- 2023

- 2023

- 2024

- 2024

- 2024

- 2025

- 2025

- 2025

- 2026

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- April

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August

- August 24

- Careering

- CERIC Supporting Organizations

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- December

- Events & Training

- F00 – Features

- F01 – Features

- F01 – Others

- F02 – Features

- F03 – Features

- F04 – Features

- F05 – Features

- F06 – Features

- F07 – Features

- F08 – Features

- F09 – Features

- F10 – Features

- F10 – Others

- F11 – Features

- F11 – Others

- F12 - Features

- F12 - Others

- F13 - Department

- F13 - Features

- F14 - Department

- F14 - Features

- F15 - Department

- F15 - Features

- F16 - Department

- F16 - Features

- F17 - Department

- F17 - Features

- F18 - Department

- F18 - Features

- F19 - Department

- F19 - Features

- F20-Department

- F20-Features

- F97 - Features

- F98 – Features

- F99 – Features

- Fall 1997

- Fall 1998

- Fall 1999

- Fall 2000

- Fall 2001

- Fall 2002

- Fall 2003

- Fall 2004

- Fall 2005

- Fall 2006

- Fall 2007

- Fall 2008

- Fall 2009

- Fall 2010

- Fall 2011

- Fall 2012

- Fall 2013

- Fall 2014

- Fall 2015

- Fall 2016

- Fall 2017

- Fall 2018

- Fall 2019

- Fall 2020

- Fall 2021

- Fall 2022

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- February

- GSEP Corner

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- january

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- January

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- july

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- July

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- june

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- June

- March

- March

- March

- March

- March

- March

- March

- March

- March

- march

- March

- March

- March

- March

- March

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- May

- Media Releases

- News

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- November

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- October

- Past Paid Webinars

- S00 - Features

- S01 - Features

- S02 – Features

- S03 – Features

- S04 – Features

- S05 – Features

- S06 – Features

- S07 – Features

- S08 – Features

- S09 – Features

- S10 – Features

- S11 – Features

- S11 – Others

- S12 – Features

- S12 – Others

- S13 - Department

- S13 - Features

- S20 – Department

- S20 – Features

- S97 - Features

- S99 - Features

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- September

- SP00 – Features

- SP01 – Features

- SP02 – Features

- SP03 – Features

- SP04 – Features

- SP05 – Features

- SP06 – Features

- SP07 – Features

- SP08 – Features

- SP09 – Features

- SP10 – Features

- SP11 – Features

- SP11 – Others

- SP12 – Features

- SP12 – Others

- SP14 - Department

- SP14 - Features

- SP15 - Department

- SP15 - Features

- SP16 - Department

- SP16 - Features

- SP17 - Department

- SP17 - Features

- SP18 - Department

- SP18 - Features

- SP19 - Department

- SP19 - Feature

- SP21 - Articles

- SP98 - Features

- SP99 – Features

- Spring 1998

- Spring 1999

- Spring 2000

- Spring 2001

- Spring 2002

- Spring 2003

- Spring 2004

- Spring 2005

- Spring 2006

- Spring 2007

- Spring 2008

- Spring 2009

- Spring 2010

- Spring 2011

- Spring 2012

- Spring-Summer 2014

- Spring-Summer 2015

- Spring-Summer 2016

- Spring-Summer 2017

- Spring-Summer 2018

- Spring-Summer 2019

- Spring-Summer 2020

- Spring-Summer 2021

- Spring-Summer 2022

- Summer 1997

- Summer 1998

- Summer 1999

- Summer 2000

- Summer 2001

- Summer 2002

- Summer 2003

- Summer 2004

- Summer 2005

- Summer 2006

- Summer 2007

- Summer 2008

- Summer 2009

- Summer 2010

- Summer 2011

- Summer 2012

- Summer 2013

- The Bulletin

- Uncategorized

- W00 - Features

- W01 - Features

- W02 - Features

- W03 - Features

- W04 – Features

- W05 – Features

- W06 – Features

- W07 – Features

- W08 – Features

- W10 – Features

- W11 – Features

- W12 – Features

- W12 – Others

- W13 - Department

- W13 - Features

- W14 - Department

- W14 - Features

- W15 - Department

- W15 - Features

- W16 - Department

- W16 - Features

- W17 - Department

- W17 - Features

- W18 - Department

- W18 - Features

- W19 - Department

- W19 - Features

- W20 – Department

- W20 – Features

- W21 - Articles

- W97 - Features

- W98 - Features

- W99 - Features

- Webinars

- Winter 1997

- Winter 1998

- Winter 1999

- Winter 2000

- Winter 2001

- Winter 2002

- Winter 2003

- Winter 2004

- Winter 2005

- Winter 2006

- Winter 2007

- Winter 2008

- Winter 2010

- Winter 2011

- Winter 2012

- Winter 2013

- Winter 2014

- Winter 2015

- Winter 2016

- Winter 2017

- Winter 2018

- Winter 2019

- Winter 2020

- Winter 2021

- Winter 2022

- Winter 2022

- Winter 2023

October 6, 2021

The 70:20:10 model can help employees focus their learning and feel a sense of accomplishment Katie Williams and Jessi Haley It’s difficult for employees to find […]

October 6, 2021

Lindsay Purchase In your wildest dreams, what would you want career development to look like in Canada? What is your vision of an ideal system, mindset, […]

October 6, 2021

With activities including skills assessment, LMI research and e-portfolio development, learnings guide students to understand how they can leverage their degree to achieve their career goals […]

October 6, 2021

Ahead of the release of the Fall 2021 issue of CERIC’s Careering magazine, which explores the theme of “Career Development Reimagined,” we asked readers to send us their […]

September 29, 2021

CERIC is requesting article proposals for the Winter 2022 issue of Careering magazine, on the theme of “Career Mindsets.” New contributors are welcome, and can submit […]

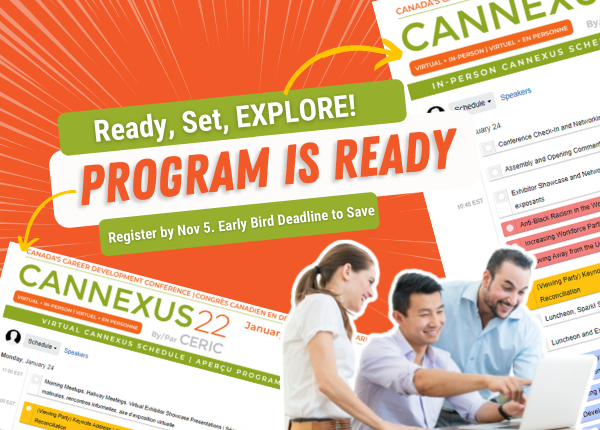

September 29, 2021

The Cannexus22 hybrid program has now been released for both the virtual edition and Ottawa-based in-person version of Canada’s largest Career Development Conference, taking place Jan. 24-26, 2022. The program includes more than 150 […]

September 13, 2021

The new issue of the Canadian Journal of Career Development (CJCD) features nine articles with a focus on schools, adolescence and young workers. Canada’s only peer-reviewed […]

September 10, 2021

Prev page

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249

Next page