Career professionals can learn how to have safe and meaningful conversations to support clients experiencing this form of bullying

Priscilla Jabouin

I was first introduced to the concept of bullying in the workplace in 2010 during my graduate course in Career Psychology. I realized that although bullying has been a workplace issue for many years, it has received very little attention in the Canadian context. Nevertheless, as a Career Counsellor in private practice, I have often heard clients share stories that highlight clear instances of this issue.

I was first introduced to the concept of bullying in the workplace in 2010 during my graduate course in Career Psychology. I realized that although bullying has been a workplace issue for many years, it has received very little attention in the Canadian context. Nevertheless, as a Career Counsellor in private practice, I have often heard clients share stories that highlight clear instances of this issue.

Unfortunately, when I researched tools to support clients in navigating this reality, the resources were very limited. This stayed with me, as I find that it reflects how our society often approaches “negative” topics. For example, in 2003, the Canadian government conducted an Ethnic Diversity Survey (EDS) and reported that 65% of underrepresented individuals experienced racism in the workplace. Even though this is a high percentage and it’s a known fact that racism has a serious impact on a person’s mental health, I did not find any follow-up action plans to deal with this situation – until now. In this post-George Floyd era, when racism and systemic racism are a hot topic, we are now witnessing everyone jumping on the equity, diversity and inclusion train.

But are we really implementing lasting solutions to this problem?

I would like to open up the discussion on a topic that is often overlooked: racism as a form of bullying in the workplace. By starting this conversation, my hope is that as career development professionals, you will be better equipped to have safe and meaningful conversations with your clients, and to help them set boundaries to protect themselves from various forms of bullying in the workplace and to limit its negative effects on their mental health.

What is bullying?

In the literature, bullying is described as a series of negative behaviours that includes harassing, offending, socially excluding or negatively affecting someone’s work, taking place repeatedly and regularly over a period of at least six months (Podsiadly, A. & Gamian, Wilk, M., 2017; Samnani, A-K. & Singh, P., 2012; High, A., Hansen, A.M., Mikkelsen, E.G., Persson, R. 2011). However, when working from a trauma-informed lens, one event is often enough for an individual to experience trauma and/or to trigger an individual’s past trauma. Therefore, it is important to recognize that an individual who experiences any type of bullying in the workplace over any period of time could still experience its negative outcomes.

In the context of this discussion, I would like to include in my definition of bullying: any type of workplace situation where an individual feels unsafe or distressed or lacks the tools to protect themself from an actual or perceived threat. In this case, I include racism as a form of bullying and as a consequence, relational trauma in the workplace.

“It is important to recognize that an individual who experiences any type of bullying in the workplace over any period of time could still experience its negative outcomes.”

The psychological impact

Research has not only confirmed that bullying in the workplace leads to negative psychological outcomes (i.e. higher rates of anxiety and depression) for individuals who are targeted by these negative behaviours (Podsiadly, A. & Gamian, Wilk, M., 2017; Samnani, A-K. & Singh, P., 2012; High, A., Hansen, A.M., Mikkelsen, E.G., Persson, R. 2011); it has also identified that targets are often ethnic minority women (Samnani, A-K., & Singh, P., 2012).

Furthermore, in its 2022 training on the trauma of racism, NICABM (National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine) emphasized the hypervigilant behaviour racialized individuals often exhibit due to the serious psychological impact of regular racial stressors in their environments. Thus, we cannot take this topic lightly if we care about the Canadian population’s mental health and well-being.

So, what can we do about it? I’d like to continue this conversation by suggesting some simple interventions you and your clients can start to use to address this problem.

Read more

The future of work for the Black community

Case Study: Reimagining mentorship for South Asian & Tamil women and gender-diverse peoples

Hiring a Chief Diversity Officer isn’t enough to make workplaces safer for racialized employees

Interventions and solutions

It can be challenging to recognize that your client is experiencing racism in the workplace; it can also be difficult for your client to acknowledge that they are being bullied at work. Therefore, I believe it’s important to highlight that it is never the “victim’s” fault or responsibility to find solutions and interventions to issues of racism, discrimination and racial micoragressions in the workplace. We do not ask the person who is bullied to come up with solutions, so let’s ensure we take the same approach when it comes to racism in the workplace.

Educating employers and employees

It should no longer be acceptable for employers to lack training and/or education on issues surrounding equity, diversity and inclusion in the workplace. To create a safe space for all leaders and employees, it should be mandatory for everyone to receive training on bias and anti-racism in the workplace. Employers need to question their current practices and go beyond simply reaching their employment equity quotas – a practice that does not protect underrepresented individuals. On the contrary, individuals can experience serious repercussions when they are tokenized and thrown into unsafe work environments where their colleagues have not explored their personal biases.

Acknowledge complaints

If you are a non-racialized individual, or your client is working with a non-racialized supervisor, it is important to remember that your experience of power and privilege means you are not in a position where you have experienced what racism looks like, feels like or sounds like. This lack of awareness can lead you to ignore serious complaints that require your immediate attention.

Denying an act of racism can be as harmful as the actual racist experience your client has endured. Remember that calling out racism requires a lot of courage from a racialized individual and puts them in a very vulnerable space, emotionally and psychologically. Treat every complaint with the amount of attention it deserves.

Understanding microaggressions

It is also important to remember that microaggressions are very subtle acts, incidents or comments that cannot be easily identified – (see Microaggressions in Everyday Life by D.W. Sue & L. Spanierman). Some things are felt in the body, and not easily explained by the mind.

Setting boundaries

This is where you can teach your client strategies to protect themselves against racism in the workplace. How can you help your clients identify safe working spaces? How can clients voice their concerns and opinions to encourage positive change in the workplace? When should a client consider leaving a toxic work environment? How can you support your client to ask questions such as: What anti-racist policies are in place? How do these translate in the workplace?

Co-operation and commitment

Is your client’s employer ready for open and uncomfortable conversations? Are they ready to hear suggestions from the groups affected by racism and discrimination? Are they ready to dive into the complexities and subjective realities of their employees? Have you prepared yourself as a helper to explore these ideas and to be in an uncomfortable space with your clients?

In order to create meaningful and positive changes in the workplace and to ensure safe work environments, employers as well as the work environments and culture need to be open and willing to listen and communicate with racialized individuals about their experience.

Conclusion

The interventions and strategies I have shared only scratch the surface of the conversation that needs to be had about racism as a form of workplace bullying. As Canadians, we will have to participate in in-depth discussions to shift mindsets and dismantle the systems that uphold work environments that are conducive to bullying and racism. If we want to create meaningful changes where the goals of equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives are optimally reached, we will have to do the uncomfortable work.

Priscilla Jabouin, M.A., C.C.C., c.o. After a career change in 2010, Priscilla returned to school to complete her master of arts in counselling psychology. She then embarked on a new path as a Career Counsellor in university career centres in Canada and the United States, and is now in private practice helping creative professionals who are unhappy at work, wake up to a career they love.

Additional sources

Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute (CTRI) (2021). Trauma: Counselling Strategies for Healing and Resilience (Training Manual)

Khan, C. (2006, Summer). “The Blind Spot”: Racism and Discrimination in the Workplace. In J.S. Frideres (vol. 2). Our Diverse Cities. (pp. 61 – 65). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anita-Friesen/publication/332180728_Winnipeg’s_Inner_City_Research_on_the_Challenges_of_Growing_Diversity/links/5ca4db0da6fdcc12ee9113e9/Winnipegs-Inner-City-Research-on-the-Challenges-of-Growing-Diversity.pdf#page=63

The past few years have been stressful, to say the least. We have had to navigate numerous challenges including but not limited to working through a pandemic while managing multiple responsibilities, witnessing and protesting social justice issues that continue to have a negative impact on disadvantaged groups and losing loved ones. The psychological impact of these stressors has tested us in many ways.

The past few years have been stressful, to say the least. We have had to navigate numerous challenges including but not limited to working through a pandemic while managing multiple responsibilities, witnessing and protesting social justice issues that continue to have a negative impact on disadvantaged groups and losing loved ones. The psychological impact of these stressors has tested us in many ways.

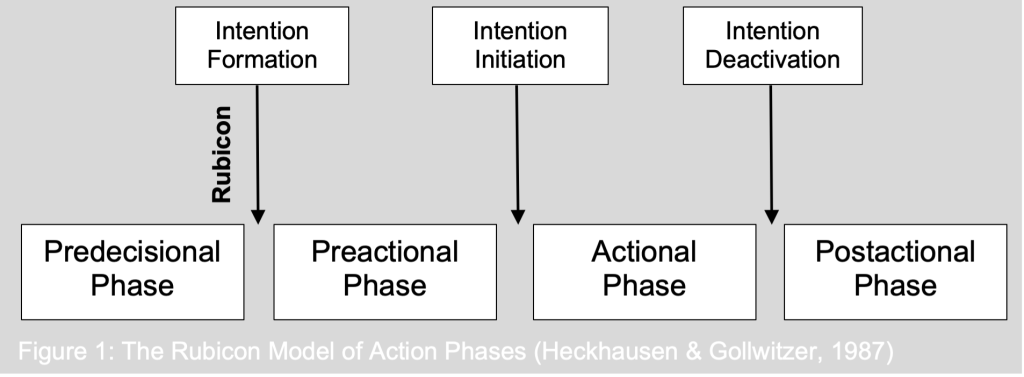

Julian is a Canadian professional soccer player whose career goal is to get into a European club. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he felt the constant stress of having to isolate when a team member was sick and started feeling disenchanted about having to play without an audience. Things are more “normal” now, but he has not been performing well and has suffered repeated injuries. Thus, he gets anxious about his performance and career goal. He often ruminates about his mistakes and wonders whether he should disengage from his goal or not. He is experiencing a career action crisis.

Julian is a Canadian professional soccer player whose career goal is to get into a European club. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he felt the constant stress of having to isolate when a team member was sick and started feeling disenchanted about having to play without an audience. Things are more “normal” now, but he has not been performing well and has suffered repeated injuries. Thus, he gets anxious about his performance and career goal. He often ruminates about his mistakes and wonders whether he should disengage from his goal or not. He is experiencing a career action crisis.

In 2020, CERIC released a series of

In 2020, CERIC released a series of

I was first introduced to the concept of bullying in the workplace in 2010 during my graduate course in Career Psychology. I realized that although bullying has been a workplace issue for many years, it has received very little attention in the Canadian context. Nevertheless, as a Career Counsellor in private practice, I have often heard clients share stories that highlight clear instances of this issue.

I was first introduced to the concept of bullying in the workplace in 2010 during my graduate course in Career Psychology. I realized that although bullying has been a workplace issue for many years, it has received very little attention in the Canadian context. Nevertheless, as a Career Counsellor in private practice, I have often heard clients share stories that highlight clear instances of this issue.